Main Body

21 Two-part counterpoint

Learning goals for Chapter 21

In this chapter, we will learn:

- General guiding principles common to examples of two-part counterpoint in a variety of tonal styles

- How to analyze interval content and motion between parts in two-part counterpoint

- Strategies for writing two-part counterpoint

Counterpoint

The term “” comes from the Latin “contrapunctus,” meaning “note against note.” Whenever two or more melodies sound at the same time, we consider this an example of counterpoint. The term was first used in the fourteenth century to describe the combination of simultaneously sounding musical lines according to a system of rules. Sets of rules governing how counterpoint works vary among different tonal styles and time periods. This chapter seeks to lay out the most general guiding principles for counterpoint with two parts, which are shared among a wide range of tonal styles. The most important concepts related to understanding contrapuntal structure include (1) and , and (2) .

Consonance and dissonance

The concepts of and , as applied to formed between two parts, will help to guide our understanding of counterpoint. are generally considered to be stable or create “agreement,” bringing tonal resolution. Perceptions of consonance differ among styles and time periods; this chapter will consider consonant intervals to be the P1, P5, and P8, and the mi3, MA3, mi6, and MA6.

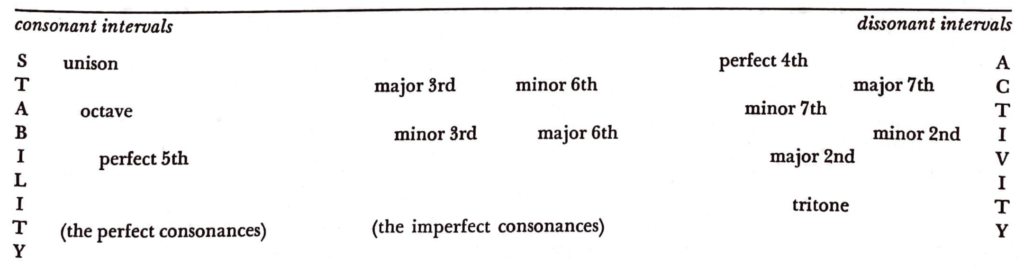

are generally considered to be unstable or create “disagreement,” bringing tension and impelling the music forward to a more stable point. This chapter will consider dissonant intervals to be the P4, mi2, MA2, mi7, MA7, and (A4/d5). To illustrate one perception of consonance and dissonance, as they relate to intervals, scholar Leo Kraft offers a continuum, in which every interval is placed according to its degree of “stability” or “activity.” This chart appears in Figure 21-1.

Figure 21‑1. Leo Kraft’s consonance and dissonance chart[1]

In general, dissonant intervals need to be treated with care because of their instability. To this end, it is best to approach and resolve dissonant intervals by step to a consonant interval.

Types of motion

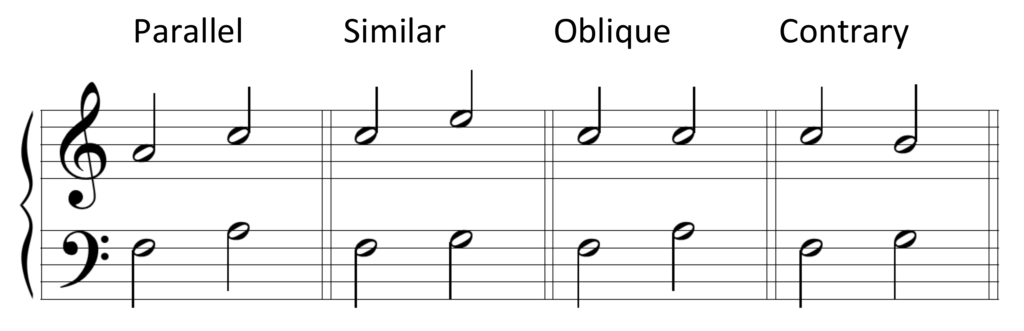

Understanding the between two parts is critical to understanding how counterpoint works. There are four types of motion:

- : motion resulting from two parts moving in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same “amount,” such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same (e.g., parallel thirds)

- : motion resulting from two parts moving in the same direction (both up or both down)

- : motion in which one part moves, while the other stays on the same pitch

- : motion resulting from two parts moving in opposite directions (one up, the other down)

Example 21-1 provides an illustration of each type of motion in musical notation. In general, we will prefer contrary and oblique motion, especially when dealing with dissonant intervals. We will use parallel motion only with .

Examples of two-part counterpoint

The best way to see how two-part counterpoint works is not necessarily to memorize lists of rules, but rather to examine different musical examples to see what general principles they have in common. If you are interested in learning how to write counterpoint in a specific tonal style, you can focus your study on a particular body of music. This chapter looks at counterpoint examples from a wide range of tonal styles and thus draws some general conclusions from what most share in common.

Example 21-2 shows a short passage of counterpoint, with annotations showing the analysis of harmonic intervals between parts. This example has the following features:

- It uses contrary and oblique motion exclusively

- It uses mostly stepwise motion in each part

- The dissonant P4 is approached and resolved by step in the lower voice while the upper voice is sustained

Example 21‑2. Annotated transcription of the Beach Boys, “Good Vibrations,” 3:13–3:19[2]

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about 20th-century American rock band the Beach Boys by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Rob C. Wegman.

Example 21‑3, an excerpt of a by Romantic composer Clara Schumann, has the following features:

- When one line is active, the other is less so

- It uses mostly stepwise motion

- Its leaps occur only when outlining chords

Example 21‑3. Clara Schumann, op. 16, Fugue no. 1 in G minor, mm. 1–7

Listen to the full track, performed by Jozef de Beenhouwer, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer and pianist Clara Schumann (1819–1896) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Nancy B. Reich and revised by Natasha Loges.

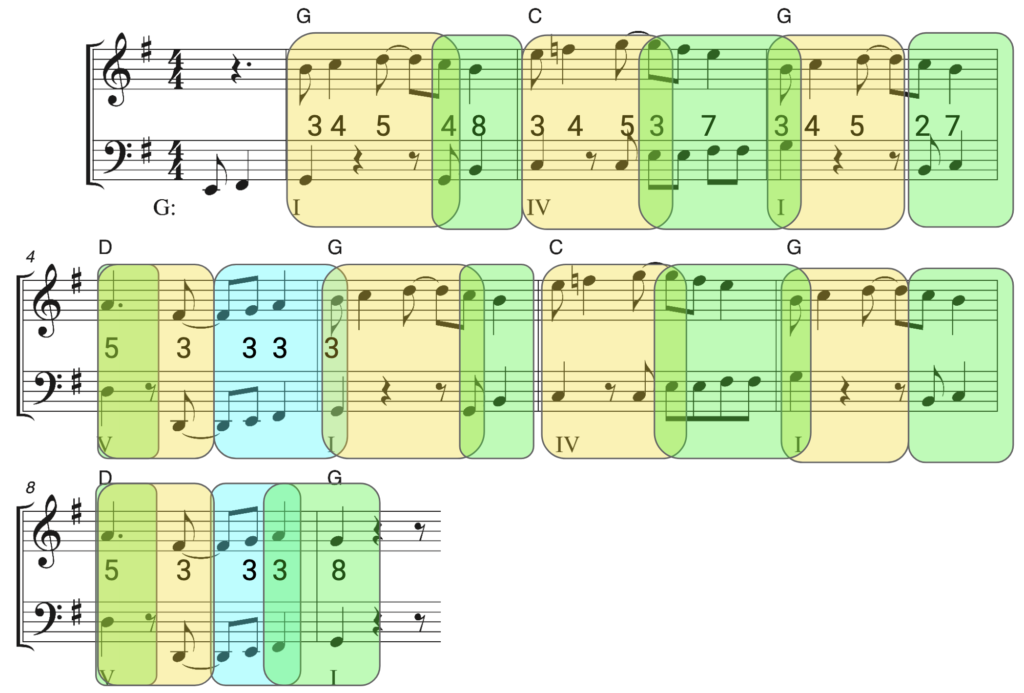

Example 21‑4 shows an excerpt by Renaissance composer Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, with annotations showing the analysis of harmonic intervals between parts. Note that the bottom staff in this example sounds an octave lower than written, because the treble clef has an “8” written just below it.[3] The example has the following features:

- Similar to Example 21-3, when one line is active, the other is less so

- It uses mostly stepwise motion

- All dissonant intervals (highlighted in the example) resolve by step to consonant ones

Example 21‑4. Annotated score for Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, Bicinium no. 1, mm. 1–8[4]

Listen to the full track, performed by Ensemble Baroque du Savès Gascon, on Spotify.

Learn about Italian composer Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi (1554–1609) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Denis Arnold and revised by Iain Fenlon.

Example 21-5, a transcription of a song by Van Morrison, features colored annotations showing different types of motion, as well as numbers indicating an analysis of harmonic intervals between parts. The colored highlighting indicates motion: oblique motion in yellow, contrary motion in green, and parallel motion in blue. The notable features of Example 21-5 include:

- Use of on downbeats

- Use of in the first half of each bar, shown in yellow

- Use of in the last half of each bar, shown in green

- Limited use of with imperfect consonances only, shown in blue

- Emphasis on in melody

- Use of chord roots on downbeats in the bass

Example 21-5 also features links to black-and-white renderings of each type of motion beneath the audio.

Example 21-5. Annotated transcription of Van Morrison, “Brown Eyed Girl,” 0:00–0:16

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Access black and white image showing oblique motion: Ex 21.5b oblique motion

Access black and white image showing contrary motion: Ex 21.5c contrary motion

Access black and white image showing parallel motion: Ex 21.5d parallel motion

Learn about Northern Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison (b. 1945) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Stephanie Conn.

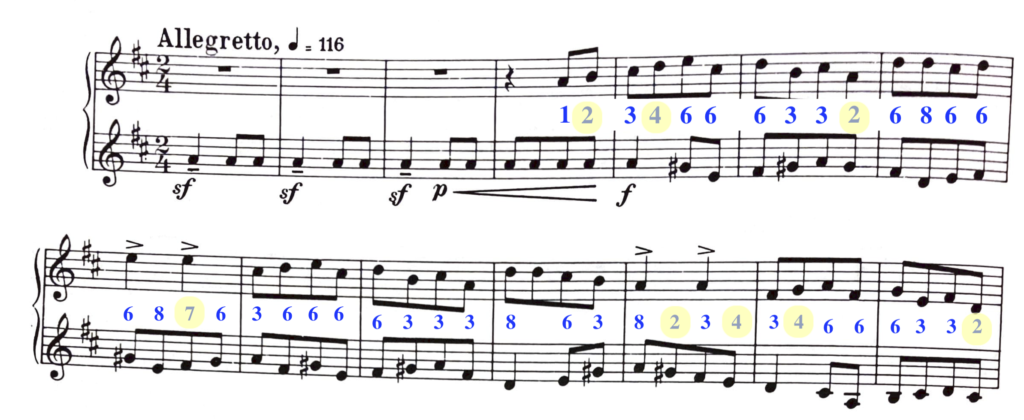

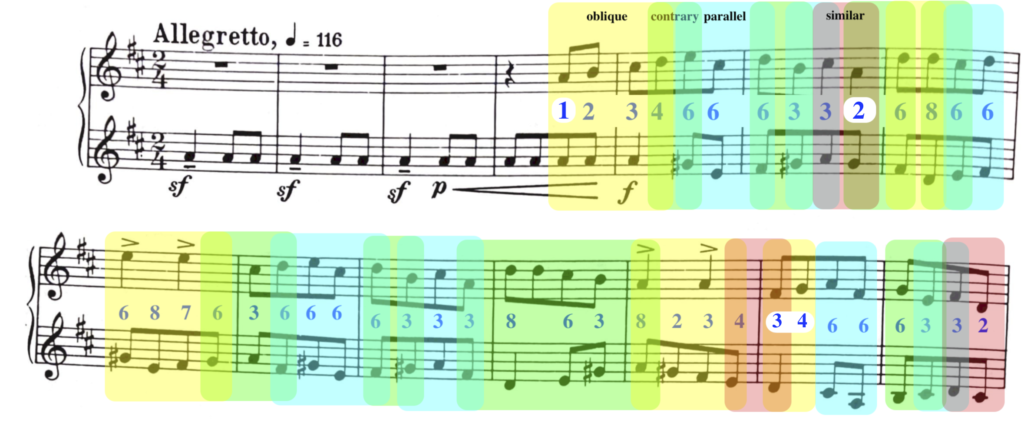

Example 21-6 shows an analysis of harmonic interval content in a lively duet for two violins by Béla Bartók. Most dissonant intervals, highlighted in the example, are approached and resolved by step to a consonant interval, and they are used sparingly. Example 21-7 shows the same excerpt with annotations showing types of motion. Observe the following features:

- Oblique motion, highlighted in yellow, and contrary motion, highlighted in green, are used more than any other type of motion

- The only harmonic intervals used with parallel motion, highlighted in blue, are sixths and thirds (imperfect consonances)

- Similar motion, highlighted in red, is used the least in this example

Example 21-7 also features links to black-and-white renderings of each type of motion.

Example 21‑6. Analysis of harmonic interval content in Béla Bartók, 44 Duos for Two Violins, no. 14 “Párnas Tánc” (“Cushion Dance”), mm. 1–14

‘XIV. Párnas Tánc’ (‘Cushion Dance’) from 44 Duos for Two Violins

Composed by Bela Bartok

© 1933 Boosey & Hawkes

Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes

Listen to the full track, performed by violinists Wanda Wilkomirska and Mihály Szűcs, on Spotify.

Learn about Hungarian composer Béla Bartók (1881–1945) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Malcolm Gillies.

Example 21‑7. Types of motion in Béla Bartók, 44 Duos for Two Violins, no. 14 “Párnas Tánc” (“Cushion Dance”), mm. 1–14

‘XIV. Párnas Tánc’ (‘Cushion Dance’) from 44 Duos for Two Violins

Composed by Bela Bartok

© 1933 Boosey & Hawkes

Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes

Access black-and-white image showing oblique motion: Ex 21.7b oblique motion

Access black-and-white image showing contrary motion: Ex 21.7c contrary motion

Access black-and-white image showing parallel motion: Ex 21.7d parallel motion

Access black-and-white image showing similar motion: Ex 21.7e similar motion

EXERCISE 21-1 Counterpoint analysis

Study and listen to each of the following excerpts, and then answer the questions and complete the tasks that follow.

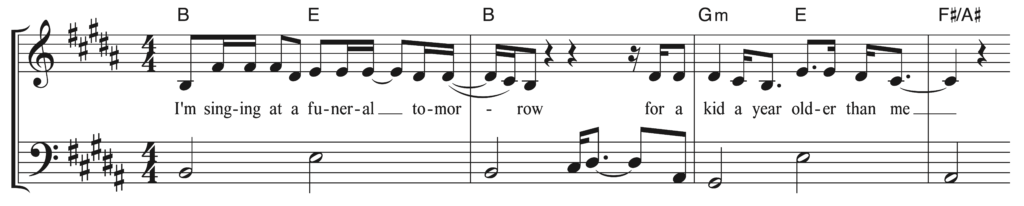

Worksheet example 21-1. Simplified transcription of Phoebe Bridgers, “Funeral,” 0:36–0:48

Questions for Worksheet example 21-1:

- Study the interval content between the bass line (bottom staff) and the vocal line (top staff). In between the staves, write the numbers representing each harmonic interval.

- Identify the interval labels that are dissonant and circle them. For each dissonant interval, consider the following questions:

a) Does the primary note involved in the dissonance resolve by step?

b) Does the dissonance resolve to a consonant interval? - Consider harmony. Based on the lead sheet symbols above the staff and thinking in the key of B major, provide Roman numerals beneath the staff to show chord function. For any inverted chords, please also use figured bass to show the inversion.

- What type of cadence occurs at the end of this excerpt?

Worksheet example 21-2. Etienne Ozi, Six duos pour deux bassons, Duo 5, Rondo: Allegretto, mm. 1–16

Listen to the full track, performed by bassoonists Dillon Meacham and Patrick Broder, on YouTube.

Learn about French bassoonist and composer Etienne Ozi (1754–1813) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Harold E. Griswold.

Questions for Worksheet example 21-2:

- What key is this excerpt in?

- Study the interval content between the parts. In general, which type of interval—perfect consonances, imperfect consonances, or dissonances—is used most?

- Study the motion between parts. In general, which type of motion—contrary, oblique, similar, or parallel—is used more than any other?

- Compare mm. 1–8 to mm. 9–16. How are these two subsections related?

- Consider implied harmony. If we hear cadences every four bars, what type of cadence is implied at the beginning of m. 4? In mm. 7–8? In m. 12? In mm. 15–16?

Writing two-part counterpoint

From this sample of excerpts we have studied, we can draw some general principles to guide our own writing of music in two parts. While these are not immutable rules, best practices include:

- Use mostly stepwise motion

- Leaps should generally outline chord tones

- Strive for rhythmically independent lines—when one line is active, consider using less activity in the other part

- Successive dissonances are rare (don’t do it)

- Prepare and resolve dissonances by step to a consonant interval

- Prefer contrary and oblique motion

- Use parallel motion only with successive thirds and sixths

As in the Bartók example, when contrary and oblique motion are used with stepwise motion in one or both parts, and there are no successive dissonant intervals, you can’t go wrong!

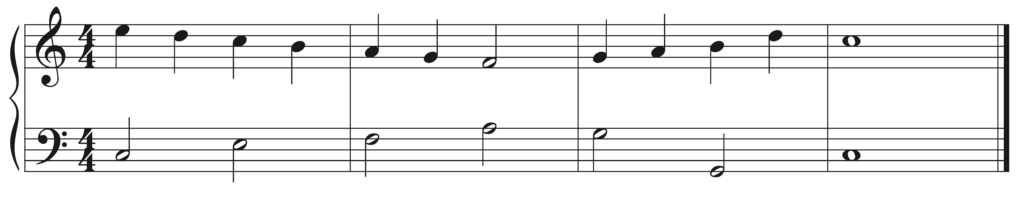

Example 21-8 shows three different solutions for writing a contrapuntal line against a pre-existing melody. The first passage, labeled “given passage,” presents the pre-existing melody. After listening to and studying it, we identify the key as C major and likely understand its harmonic implication as I – IV – V – I, with a harmonic rhythm of one chord per bar. Each of the next three passages presents one possible solution in the upper staff with a different rhythmic relationship to the given line, moving more quickly (Solution 1), more slowly (Solution 2), and at the same rate of motion (Solution 3).

Example 21‑8. Model with three solutions for writing two-part counterpoint

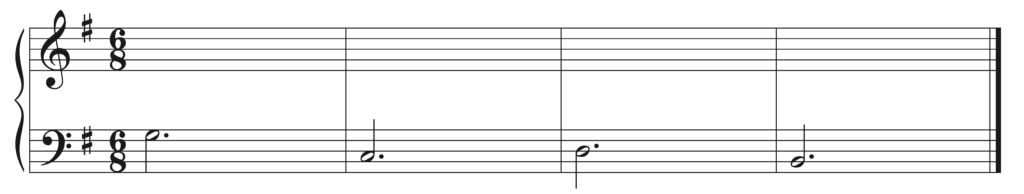

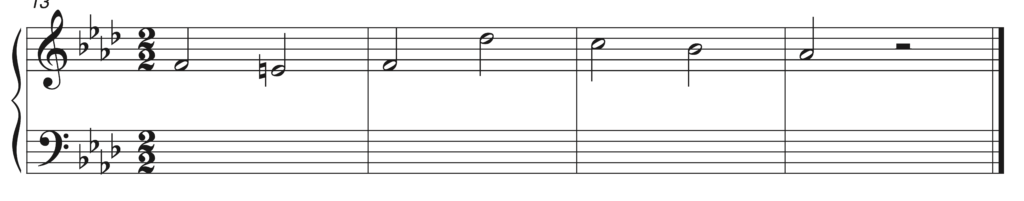

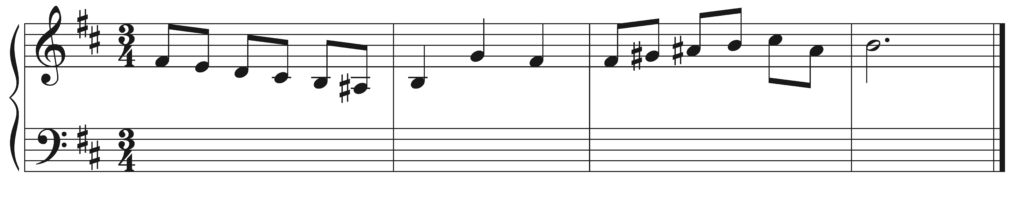

EXERCISE 21-2 Writing two-part counterpoint

For each passage, study the melody already written for you and identify the key. Then, on the blank staff provided, write a melody against this part to create counterpoint. Do not change the given melody. Pro tip: When one part is more rhythmically active, it often works well to write a less rhythmically active part in counterpoint to it. Be sure to follow the counterpoint principles we’ve studied:

- Start and end on a consonant interval

- Use more stepwise motion than leaps

- Restrict leaps to outlining chord tones (all notes approached by leap should be consonant with the other part)

- Prefer contrary and oblique motion, unless using successive imperfect consonances (thirds and sixths) in parallel motion

- Prepare and resolve all dissonances by step to a consonant interval

Also, follow these principles, which relate to tonal aspects of melody construction:

- When in a minor key, raise the leading tone (scale degree

, as in harmonic or ascending melodic minor)

, as in harmonic or ascending melodic minor) - Do not double the leading tone (it’s too unstable to have sounding at the same time in both parts)

- Have at least one part end on the tonic scale degree

Passage 1:

Passage 2:

Passage 3:

Passage 4:

Passage 5:

Supplemental resources for Chapter 21

- Leo Kraft, Gradus (New York: W.W. Norton, 1976), 29. ↵

- Adaptation of transcription by Kevin Holm-Hudson, Music Theory Remixed : A Blended Approach for the Practicing Musician (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 141. Adapted with the permission of the author, annotations mine. ↵

- This is the same clef symbol used in choral music today for most tenor parts. ↵

- "Bicinium No.1 (Gastoldi, Giovanni Giacomo)" by Allen Garvin is licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0 Annotations are mine. ↵

any process in which two or more melodies sound at the same time, usually according to a system of rules specific to a particular tonal style

tonal stability, agreement, and/or that which brings tonal resolution

tonal instability, disagreement, and/or that which brings tonal tension

the four ways in which two melodic lines may interact with one another: (1) parallel, (2) similar, (3) contrary, or (4) oblique

two notes played simultaneously (in contrast to melodic intervals, which are played successively)

intervals that are considered stable, or those that function as “agreement,” bringing tonal resolution; consonant intervals are P1, P5, P8, mi3, MA3, mi6, and MA6

the intervals P1, P5, and P8, as well as their compound interval equivalents

intervals including mi3, MA3, mi6, and MA6

intervals considered to be unstable, or those that function as “disagreement,” bringing tension, impelling the music forward to a more stable point; dissonant intervals include the P4, mi2, MA2, mi7, MA7, and tritone

term referring to the dissonant interval, the A4, and its enharmonic equivalent, d5

motion resulting from two parts moving in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same “amount” such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same number/size (e.g., parallel thirds)

for intervals, the number of steps between two notes, including the starting and ending note

motion resulting from two parts moving in the same direction (both up or both down)

motion in which one part moves, while the other stays on the same pitch

motion resulting from two parts moving in opposite directions (one up, the other down)

compositional process using short musical subjects, alternating sections using strict imitation and episodic sections in free counterpoint

notes belonging in a chord; e.g., the chord tones in a major triad are C, E, and G