Main Body

5 Intervals

Learning goals for Chapter 5

In this chapter, we will learn:

- How to construct and identify intervals

- How to use interval inversion

- How to aurally identify intervals

Major and minor intervals

An measures the distance between two pitches and consists of two parts, a (a number) and a (major, “MA” or “M”; minor, “mi” or “m”; perfect, “P”; diminished, “d” or “o”; or augmented, “A” or “+”).

Quantity. To determine the quantity of an interval, simply count the number of lines and spaces between two notes on the staff, including the notes themselves. Some examples of this process are shown in Example 5‑1.

Quality. Determining the quality of an interval is more complicated than determining the quantity. There are two basic types of classification: and . Each interval quantity fits into only one classification: for (those of an octave or smaller), seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths are major/minor, and unisons, fourths, fifths, and octaves are perfect.

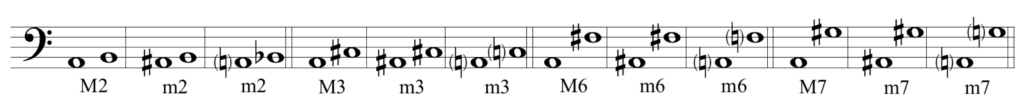

Major and minor intervals. We have studied some intervals already—the half step and whole step. Using the major/minor classification system, we call a half step a minor second (mi2) and a whole step a major second (MA2). Thirds may be understood as combinations of seconds. A minor third (mi3) is equivalent to three half steps or MA2+mi2. A major third (MA3) is equivalent to four half steps or two MA2s.

If you think of the lower note of an interval as tonic of a major scale, you can use that scale to identify any major interval. Example 5-2 shows this technique: A is the lowest note of each interval in this case, so we use the A major scale to determine the higher note.

Minor intervals are always a half step smaller than major ones. Example 5‑3 shows how to derive minor intervals from the major ones by reducing their size by one half step. This is done by either raising the lower note or lowering the higher note by one half step.

Example 5‑3. Finding minor intervals from major intervals

Sometimes large intervals can be difficult to identify. If seconds and thirds are easier for you to identify than sixths and sevenths, you may use to make the process easier. Interval inversion—creating the inversion of the original interval—works either by displacing the lower note of an interval up an octave or by displacing the higher note down an octave. Once the interval is inverted, the quality inverts (major intervals become minor and vice versa), and so does the quantity (sevenths become seconds and vice versa, and sixths become thirds and vice versa). Example 5‑4 shows how interval inversion works for major and minor intervals.

Video: T08 Intro to intervals (3:45)

This video briefly explains what intervals are, the two components involved in labeling (quality and quantity), and how to determine the size (quantity) of the interval between any two notes on the staff.

Video: T09 Major intervals (4:37)

This video shows how to construct any major interval (MA2, MA3, MA6, MA7) by thinking of the lower note as tonic of a major scale.

Video: T10 Minor intervals (5:17)

This video shows how to derive minor intervals from their corresponding major intervals by reducing the size of the major interval by one half step. This can be achieved by either lowering the top note or raising the bottom note by a half step.

Video: T11 Interval inversion (6:40)

This video shows you how to find large major and minor intervals (sixths and sevenths) through a process called “interval inversion,” relating them to thirds and seconds respectively. Seconds invert to sevenths, and thirds invert to sixths. Major intervals invert to minor ones, and vice versa.

EXERCISE 5-1 Drills with major and minor intervals

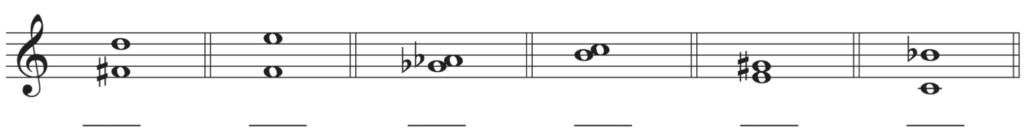

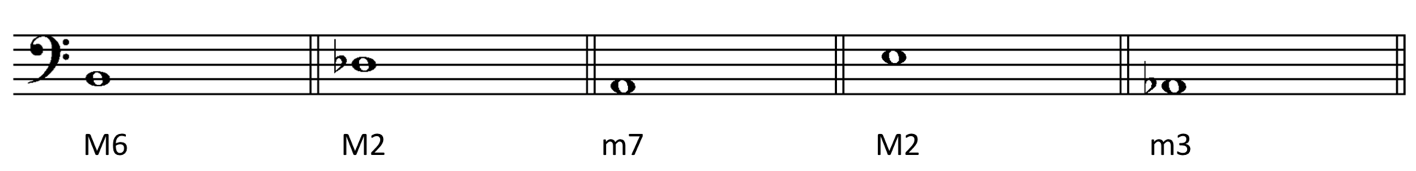

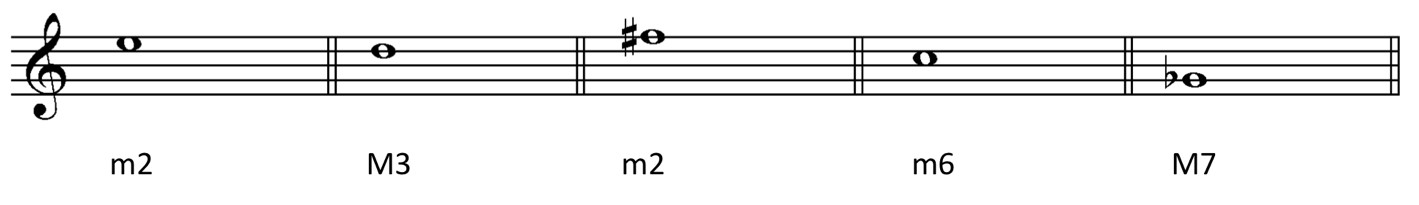

PART A. Complete the following intervals, given the lower note.

SET 1

SET 2

PART B. Provide the label (quality and number) for the following intervals.

SET 3

SET 4

Want more practice with major and minor intervals? Try these drills:

Practice constructing major and minor intervals (teoria)

Practice identifying major and minor intervals (teoria)

Practice identifying major and minor intervals and their inversions (teoria)

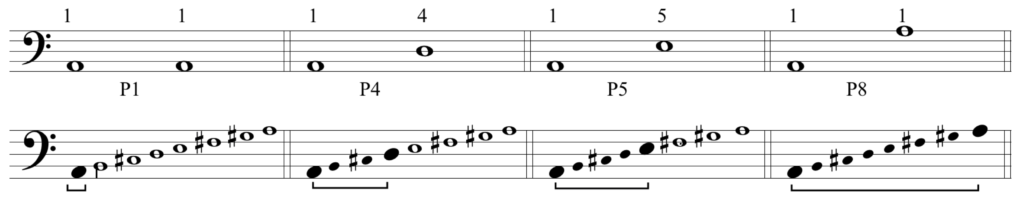

Perfect intervals

Perfect intervals include unisons, fourths, fifths, and octaves. Like with major intervals, you can identify any perfect interval from a major scale by thinking of the lower note as tonic of the scale. Example 5-5 shows this technique: A is the lowest note of each interval, so we use the A major scale to determine the higher note in each case.

Example 5‑5. Perfect intervals derived from the major scale

Using , fourths invert to fifths and vice versa, and unisons invert to octaves and vice versa. Unlike with major and minor intervals, quality does not change when a perfect interval is inverted.

Video: T12 Perfect intervals (9:05)

This video shows how to derive any perfect interval (P1, P8, P4, or P5) from a major scale by thinking of the lower note as tonic of the scale.

Diminished and augmented intervals

Major, minor, and perfect intervals may be modified in additional ways to create and intervals, which are less common than the other interval qualities.

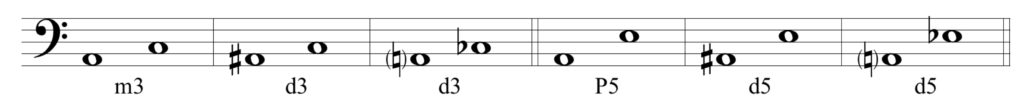

A interval results when either a minor or perfect interval is made smaller by one half step. This is done either by raising the lower note or lowering the higher note by one half step, as shown in Example 5‑6.

An interval results when either a major or perfect interval is made larger by one half step. This is done by either lowering the lower note or raising the higher note by one half step, as shown in Example 5‑7.

Using , augmented intervals invert to diminished ones and vice versa. Quantities invert in the same way as major, minor, and perfect intervals (seconds become sevenths, thirds become sixths, fourths become fifths, and so forth). No matter what the interval, its own quantity and the quantity of its inversion always add up to nine.

Video: T13 Augmented and diminished intervals (8:58)

This video shows how to get augmented intervals by making a major or perfect interval one half step larger, and how to get diminished intervals by making a minor or perfect interval one half step smaller.

Compound intervals

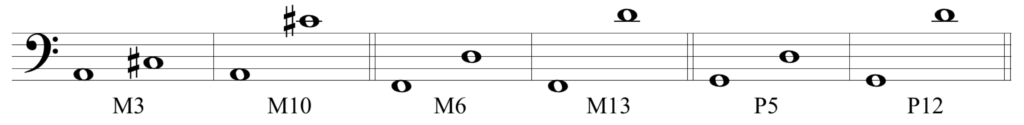

The previous examples deal with , which are intervals that are an octave or smaller. are intervals that are larger than an octave. Convert any simple interval to a compound one by adding seven to its quantity and displacing the higher note by one octave, as shown in Example 5‑8.

Example 5‑8. Simple intervals and their compound counterparts

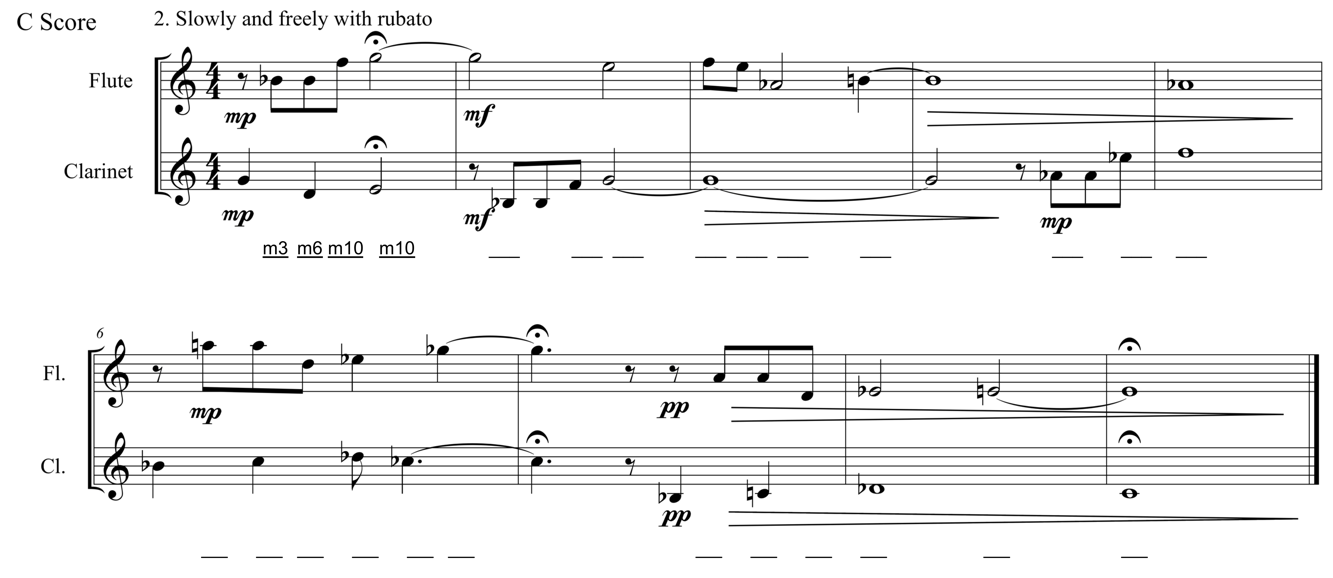

EXERCISE 5-2: Analysis of Judith Cloud, Six Forays for Flute and Clarinet, mvt. 2

Listen to Judith Cloud’s Six Forays for Flute and Clarinet and provide labels for each harmonic interval formed between the flute and clarinet in the score below. The first measure is done for you.

Worksheet example 5‑1. Judith Cloud, Six Forays for Flute and Clarinet, mvt. 2

Want more practice identifying intervals? Try these drills:

Practice identifying all intervals in various clefs (teoria)

Practice identifying all intervals in various clefs (musictheory.net)

Identifying intervals aurally

Learning how to identify intervals aurally can be a daunting task. If this is a goal you wish to achieve, I offer here some techniques for mastering aural interval identification. A combination of three different techniques—song association, tonal implication, and degree of dissonance—may be used for optimum success.

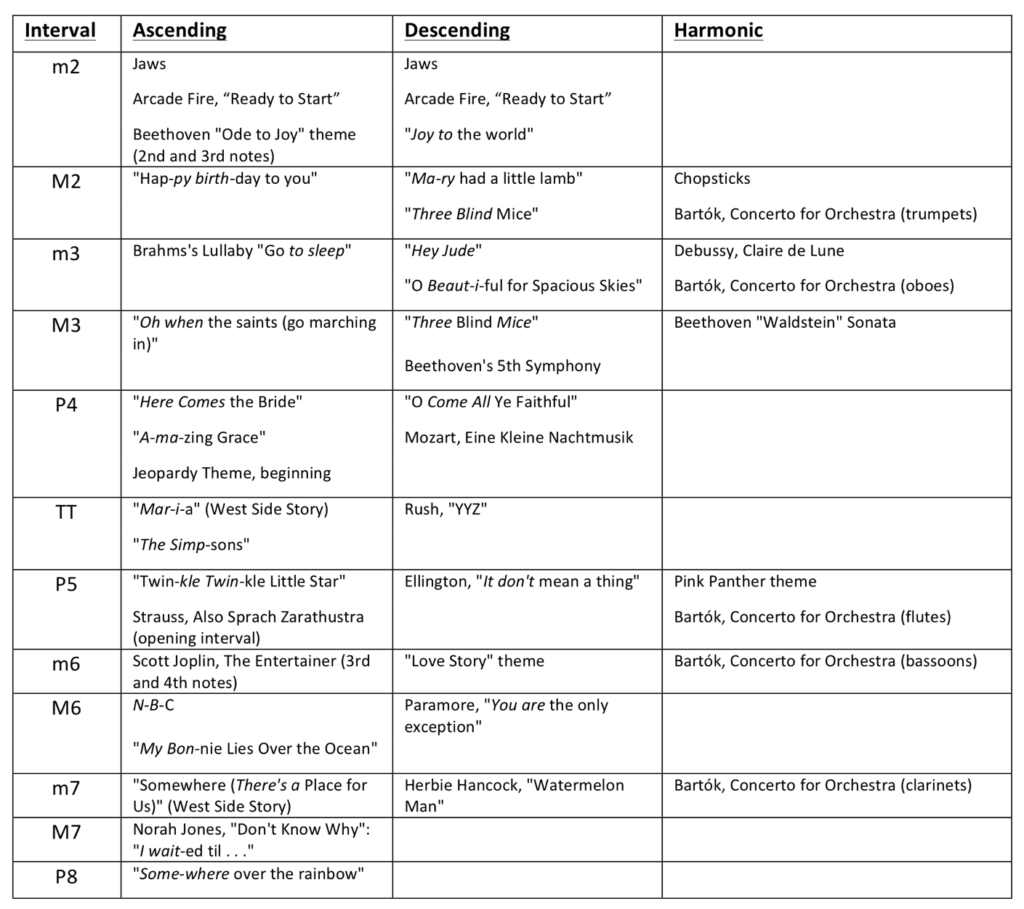

Song association

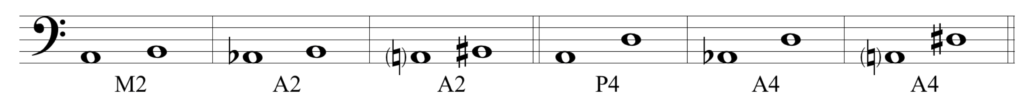

Are there particular intervals that you have difficulty identifying? Try associating the interval with a catchy tune that you already know. Figure 5‑1 summarizes some common musical themes with ascending, descending, and harmonic intervals. You can add your own favorite tunes to this chart, as needed.

Figure 5‑1. Song association interval chart

Tonal implication

Depending on an interval’s context (, register placement, and so forth), using song associations may not always render successful results. However, with a solid knowledge of relative pitch relationships through solfege, you can learn to identify intervals. Figure 5‑2 relates intervals to their most common usages in tonal music.

Figure 5‑2. Tonal implication interval chart

Degree of dissonance

For millennia, scholars have examined the properties of intervals, often classifying them as dissonant or consonant. Some intervals have been considered dissonant during one era and later considered consonant, and vice versa. Active in the 20th century, composer, theorist, and pedagogue Paul Hindemith created a table (called “Series 2”) that places intervals along a continuum ranging from most consonant to most dissonant. This table is reproduced in Figure 5‑3.

Figure 5‑3. Hindemith’s “Series 2”[1]

You can listen for an interval’s degree of consonance or dissonance to help you aurally identify it. Pedagogue and scholar Rudy Marcozzi has developed a strategy for interval identification based on binary logic. His flowchart summarizing binary decision-making appears in Figure 5‑4.

Figure 5‑4. Marcozzi’s interval flowchart[2]

Want practice identifying intervals by ear? Try one of these online drills:

Interval ear trainer (tonesavvy)

Interval ear trainer (teoria)

Interval ear trainer (musictheory.net)

Supplemental resources for Chapter 5

the measure of distance between two pitches

for intervals, the number of steps between two notes, including the starting and ending note

for intervals and chords, the specific configuration of interval content resulting in a unique and identifiable sound; for intervals, quality may be major, minor, perfect, diminished, or augmented; for triads, quality may be major, minor, diminished, or augmented; and for seventh chords, quality may be major, major-minor (dominant), minor, half-diminished, or fully diminished

qualities that can describe intervals, scales, or chords; with regard to intervals, this pairing refers to simple intervals of seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths and their compound interval equivalents

with regard to intervals, the quality of simple intervals of unisons, fourths, fifths, and octaves, as well as their compound interval equivalents

intervals smaller than a ninth: unisons (1), seconds (2), thirds (3), fourths (4), fifths (5), sixths (6), sevenths (7), and octaves (8)

property of interval relations that occurs when the lower note of an interval is placed an octave higher, or the higher note is placed an octave lower; this relation makes major intervals minor, minor intervals major, diminished intervals augmented, and augmented intervals diminished; perfect intervals invert to perfect intervals, unisons invert to octaves, seconds invert to sevenths, thirds invert to sixths, and fourths invert to fifths

term denoting quality of an interval (one half step smaller in size than its minor or perfect counterpart), quality of a triad (comprising two minor thirds), or quality of a seventh chord

term denoting quality of an interval (one half step larger than its major or perfect counterpart), or quality of a triad (comprising two major thirds)

intervals larger than an octave

"the perceptual quality of sound” (Eidsheim 2008, 158)