Main Body

19 Phrases and periods

Learning goals for Chapter 19

In this chapter, we will learn:

- How phrases can be defined by harmonic motion and cadence type

- How successive phrases can form phrase groups or periods

- Different types of periodic structure

Phrases and periods

The analysis of musical form attempts to look beyond the minutiae of chord-to-chord construction and relate larger spans of music to one another. A is a musical passage that concludes with a cadence (, , , , or ). In addition to the necessary harmonic motion associated with each cadence, musical cadences may or may not be indicated by changes in texture, changes in (that is, the rate of chord change), or cessation of rhythmic activity.

Phrases are the musical equivalent of sentences in prose, and we can think of a cadence as the musical equivalent to a sentence’s ending punctuation. Figure 19‑1 shows roughly the punctuation equivalent to each cadence type, ranging from the most conclusive (or strongest), the PAC (!), to the most open (or weakest), the HC (?).

Figure 19‑1. Cadences and their degree of conclusiveness

When more than one phrase appears successively, several different relationships between phrases may occur. When a phrase with greater openness is followed by one with greater conclusiveness (for example, when a phrase ending with a HC is followed by one with a PAC), the two phrases are said to comprise a . Periodic construction follows a question-and-answer prototype. The first phrase of a period, called the , sets up the “question” (as it were), and the second phrase, the , provides the “answer.”

When the antecedent and consequent are quite similar (perhaps sharing the same melodic structure except for the cadence, or starting similarly), we describe the form as a . When the antecedent and consequent are significantly different, the form is a . Phrase relationships denoting degree of contrast are shown by lowercase letters in form diagrams, such as the ones shown in Figure 19‑2. If a phrase resembles a previous one, its label uses the same lowercase letter followed by a prime sign ( ′ ), as in the parallel period model. If a phrase is significantly different from the previous one, its label uses a new lowercase letter, as in the contrasting period model.

When two successive phrases end with the same cadence (for example, both ending with IACs) or when a phrase with greater conclusiveness is followed by one with greater openness (for example, a phrase ending with an IAC followed by one with a HC), the two phrases are said to comprise a .

Occasionally, a group of three phrases may form either a three-phrase period or a three-phrase phrase group. A three-phrase period results when the first two phrases function as antecedents (with weaker, or less conclusive cadences) and are followed by a single consequent phrase (having a stronger, or more conclusive cadence). A three-phrase phrase group consists of three phrases that do not have this antecedent-consequent relationship.

A results when either two periods or a phrase group and a period combine into a larger antecedent-consequent relationship. The prototypical manifestation of a double period appears in Figure 19‑3.

In a double period, the consequent of the first phrase group ends with a less conclusive cadence than the consequent of the second period. (In the model above, these cadences are HC and PAC, respectively.) These nested antecedent-consequent relationships are essential to the construction of double periods. Furthermore, there is usually some similarity among the four phrases that comprise a double period.

Self-check quiz on phrases and periods

Video: T45 Intro to phrases and periods (8:44)

This interactive video explores parallel and contrasting periods in Stephen Foster’s “Oh Susanna,” as performed by Keith Little.

Phrases and periods in “O Danny Boy”

Frederick Weatherly’s famous tune “O Danny Boy” features four clear phrases, delineated by cadences every four bars. Example 19-1 provides an analysis of the chords using Roman numerals and identifies the cadences at the end of each phrase above the staff. This piece presents two successive . Measures 1–8 comprise a . Notice the similarity in the melody of mm. 1–2 and mm. 4–5; this is what makes the first eight bars parallel. The period structure comes from the half cadence in m. 4 followed by the perfect authentic cadence in mm. 7–8. Measures 9–16 comprise a . Here we get the half cadence followed by a perfect authentic cadence (hence, a period), but the melodies begin differently, so this eight-bar segment is considered contrasting.

Example 19‑1. Annotated lead sheet for Frederick Weatherly, “O Danny Boy”

Figure 19‑4 shows the form design for this piece by using bubbles to represent phrases. Such a form diagram also shows measure numbers, cadences, and lowercase letters to show melodic relationships among phrases.

EXERCISE 19-1 Analysis with phrases and periods

After listening to and studying each excerpt, do the following:

- Label the key, Roman numerals, and cadences on the blanks provided.

- Create a form diagram for each excerpt containing the following:

• bubbles, labeled with lowercase letters, to show phrases

• cadences at the end of each phrase beneath the bubbles

• measure numbers that show where each phrase begins and ends - Complete the short online quiz that follows each excerpt to check your knowledge regarding phrase structure and form.

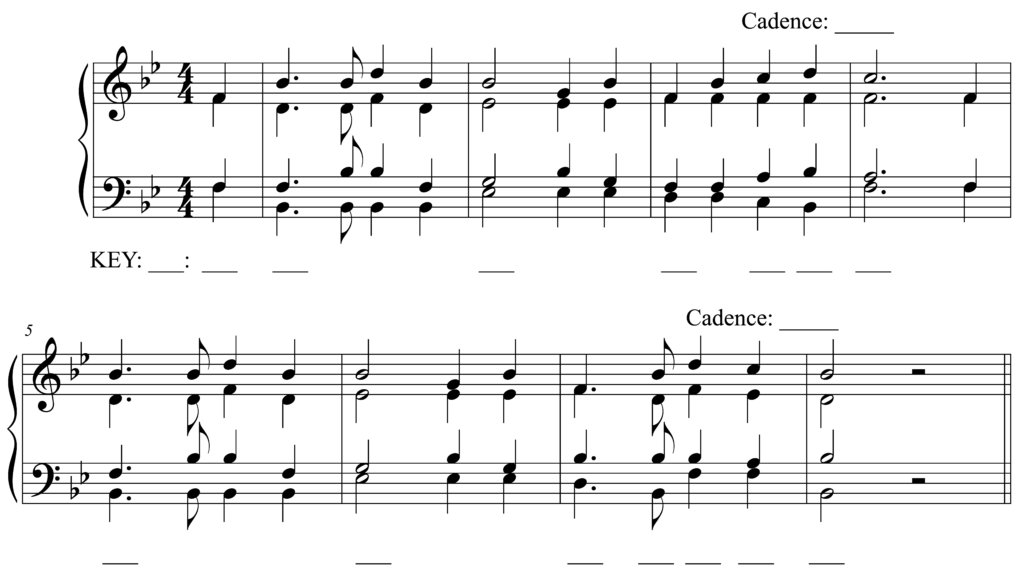

Worksheet example 19‑1. George J. Webb, “Webb,” mm. 1–8

Learn about American music educator and composer George J. Webb (1803–1887) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by William E. Boswell.

Worksheet example 19‑2. W. A. Mozart, Sonata for violin and piano, K. 377, mvt. 2, mm. 1–16

Listen to the full track, performed by Vilmos Szabadi, on Spotify.

Learn more about Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Cliff Eisen and Stanley Sadie.

Worksheet example 19‑3. Ludwig van Beethoven, Piano Sonata no. 5, op. 10, no. 1, mvt. 2, mm. 1–16

Listen to 0:00–1:10 of the recording, performed by pianist Richard Goode, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Joseph Kerman and others.

EXERCISE 19-2 Compose a parallel period

On a piece of staff paper or using a notation program, compose a melody that has a parallel period construction. Your composition should:

- Be eight measures long

- Have two similar phrases, each four measures long, both of which begin identically

- Have a first phrase that implies a HC – do this by ending on scale degree

,

,  , or

, or  in m. 4

in m. 4 - Have the second phrase imply an IAC or PAC – do this by ending on scale degree

or

or  on the downbeat of the last measure

on the downbeat of the last measure - Have a logical, tonal melody

- Have a clef, key signature, time signature, and bar lines. All systems after the first should continue to have a clef, key signature, and bar lines.

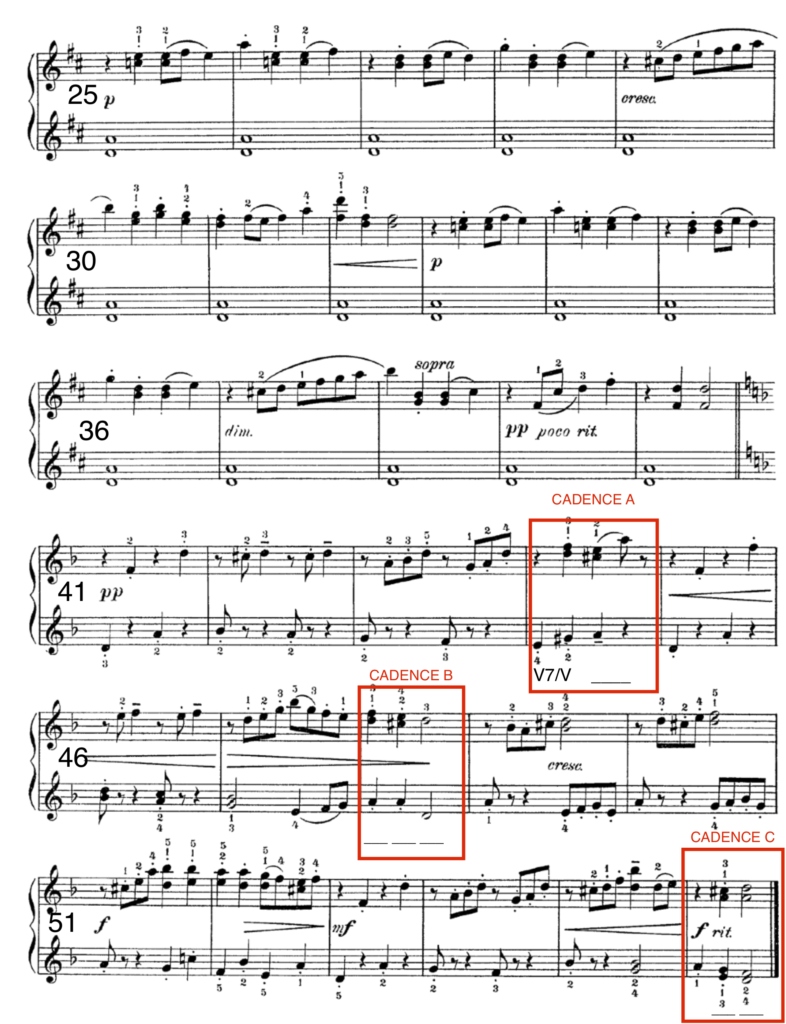

EXERCISE 19-3 Analysis of Amy Beach, Gavotte, op. 36, no. 2

After listening to and studying Worksheet example 19-4, answer the questions below.

- What key is mm. 25–40 in?

- What key is mm. 41–56 in?

- What is the relationship between the two keys in this excerpt?

- Examine m. 44. What is the missing chord label?

- What type of cadence is CADENCE A?

- Examine m. 48. Write down Roman numerals (with figured bass when a chord is inverted) for the three chords in m. 48.

- What type of cadence is CADENCE B?

- What term (two words) best describes the form of mm. 41–48?

- What type of cadence is CADENCE C? How is CADENCE C different from CADENCE B?

- Examine the right-hand part (on the upper staff). There are three in this excerpt. Write down the measure numbers of where each occurs. Specify the length of the model and how many legs follow.

Worksheet example 19‑4. Amy Beach, Gavotte, op. 36, no. 2, mm. 25–56

Listen to the full track, performed by pianist Kirsten Johnson, on YouTube.

Learn about American composer Amy Beach (1867–1944) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Adrienne Fried Block and revised by E. Douglas Bomberger.

Melodic dictation with phrases

Practice listening for form at the level of the phrase by notating melodies that use periods and other two-phrase structures. See nos. 23, 28–39, and 41–44 in Appendix D for melodic dictations that feature multi-phrase form designs.

Supplemental resources for Chapter 19

musical passage that concludes with a cadence

abbreviation for "perfect authentic cadence," which is the most conclusive cadence type, having both of the following features: (1) the cadence uses a dominant chord in root position followed by a tonic chord in root position, and (2) the tonic triad uses scale degree 1 (“do”) in the soprano melody or main melodic part

abbreviation for "imperfect authentic cadence," which refers to any cadence that moves from dominant function to the tonic triad in which any of the chords is inverted or uses the leading tone chord instead of V, or in which a scale degree other than 1 ("do") is in the highest part or melody with the tonic chord

abbreviation for "plagal cadence," which refers to the cadence type that features subdominant to tonic

abbreviation for "deceptive cadence," the term referring to a cadence that consists of two chords: dominant (V or V7) to a chord other than tonic, usually the submediant triad

abbreviation for "half cadence," the term referring to a cadence type that ends with a dominant chord

the rate of chord change

unit of form in which a phrase with greater openness is followed by one with greater conclusiveness (for example, a phrase ending with a HC followed by one with a PAC)

first phrase of a period

second phrase of a period

unit of form that features (1) two phrases—the first ending with a weaker cadence, followed by a second ending with a stronger cadence—in which (2) both the antecedent and consequent phrase begin the same way melodically

unit of form with the following features: (1) two phrases—the first ending with a weaker cadence, followed by a second ending with a stronger cadence—and (2) antecedent and consequent phrases that begin differently

unit of form consisting of two phrases that do not have an antecedent-consequent relationship; occurs when two successive phrases end with the same cadence (for example, two phrases both ending with IACs) or when a phrase with greater conclusiveness is followed by one with greater openness (for example, a phrase ending with an IAC followed by one with a HC)

unit of form in which two periods or a phrase group and a period combine into a larger antecedent-consequent relationship, where the second cadence is open (like a HC) and the fourth cadence is closed (like a PAC)

process in which a portion of music (both intervallic and rhythmic content) is successively replicated at a different pitch level