Main Body

34 Binary form

Learning goals for Chapter 34

In this chapter, we will learn:

- Terminology related to two-part forms

- How to approach analyzing pieces that have two large contrasting sections

Binary form

A piece is in if it has two large sections. When creating form diagrams, we will represent large sections with uppercase letters, in contrast to , which we represent with lowercase letters. Figure 34-1 represents a typical manifestation of binary form where the second large section (B) presents contrasting elements to the first large section (A). It shows a modulation to a new key and back to tonic, which often occurs in binary form but is not required.

Sometimes binary form is referred to a when repeat signs demarcate each section, as shown in Figure 34‑2. Although not always present, repeat signs and double bar lines can often be important visual cues to understanding the formal design of a piece.

Pieces in binary form can manifest in many different ways depending on their tonal content, presence of restated material, and length of sections. Special terminology, appearing in the descriptions below, helps us make sense of different manifestations of binary form.

Tonal content. If the A section of a binary piece can stand on its own harmonically, then it is . To be sectional, the A section must end with a conclusive cadence (either or ) in the tonic key. If the A section ends with an inconclusive cadence (such as a ), or if it ends in a different key (even if there is a conclusive cadence in the new key), the form is considered .

Presence of restated material. If no material from the A section reappears in the B section, the form is . If a portion of the A section returns at the end of the B section, the form is . Figure 34‑3 shows a typical representation of rounded binary. In this design, we still perceive two large overarching contrasting sections, as demarcated by the repeat signs and ending double bar line, but the large B section ends with A”.

A common example of rounded binary is , which can be represented as in Figure 34‑4. In this form, the B section is referred to as the .

forms offer another, but less common way of restating material. A technique found in some Baroque dance movements, balanced binary forms occur in continuous pieces when a brief portion of the end of the A section (usually stated in the key of the dominant) is restated at the end of the B section in the tonic key.

Length of sections. Binary forms are considered when both sections are the same, or nearly the same, length. When one section (usually B) is longer than the other, the form is considered .

Video: T61 Intro to binary form (8:39)

This video introduces the concept of binary form, relates its larger structure to the concept of the smaller-level continuous period, and defines important terms related to the study of pieces in binary form, including continuous and sectional, simple and rounded, two-reprise form, and 32-bar song form.

Elements of unity and contrast

Suggestion: Musicologist Jan LaRue’s book Guidelines for Style Analysis provides a detailed method for considering elements of unity and contrast when approaching analysis of form design.[1] Some of the elements listed in LaRue’s categories of “sound,” “harmony,” “melody,” and “rhythm,” summarized in Figure 34-5, are the most relevant to our analytic approach to form. You can use the list in Figure 34-5 as a checklist of things to consider that may contribute to the perception of unity and contrast between large sections.

Figure 34-5. Partial summary of Jan LaRue’s “Cue Sheet for Style Analysis”

Sound. The category of sound encompasses the following:

- timbre, including instrumentation

- range and tessitura

- texture

- dynamics

Harmony. The category of harmony encompasses the following:

- tonality

- key relationships

- “chord vocabulary,” meaning types of chords that are used—, , , and so forth

Melody. The category of melody encompasses the following:

- range

- type of motion (stepwise, leaping, chromatic, diatonic)

- patterns

- repetition

Rhythm. The category of rhythm encompasses the following:

- “surface rhythm, vocabulary and frequency of and patterns”

- meter

- segmentation (lengths of phrases and other smaller formal units)

- “”

- “”

- “patterns of change”

Cues for analysis

Whenever you encounter a new piece that appears to be in two large parts, consider the questions in Figure 34‑6, which can guide and inform your analysis.

Figure 34‑6. Cue sheet for binary form

(1) Is the form of the piece or ? If continuous, is the form ?

(2) Is the form of the piece or ?

(3) Is the design or ?

(4) What is the basic formal diagram for this piece? Draw a diagram to show the form that includes:

- measure numbers

- key areas (account for all modulations) shown as letters (e.g., CMA or Ami) as well as in Roman numerals (e.g., I or vi)

- uppercase letters to designate large sections

- slurs or bubbles labeled with lowercase letters to designate phrases

- cadence labels

- other section labels, such as or , when used

(5) Examine how the primary musical elements (melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, instrumentation, dynamics, phrasing) are used for unity and contrast between the A and B sections.

Pieces for analysis

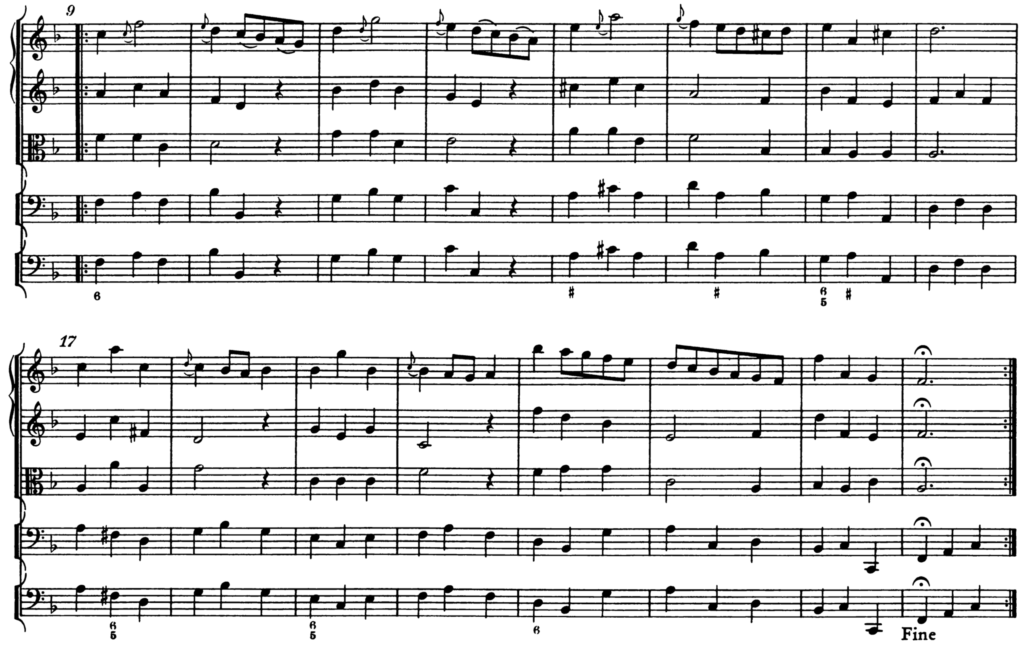

Let’s consider some of the questions in Figure 34‑6 as they apply to the movement reproduced in Example 34‑1. After listening to this movement, we can identify that it begins and ends in F major. It features a modulation to C major (a key) prior to the point of bisection (m. 9), and thus the form is continuous. No material from the A section recurs within the B section, so the form is considered simple. Its form is also considered a two-reprise form, as both sections use repeat signs to help delineate the form.

Example 34‑1. Sophia Dussek, op. 2, no. 1, Harp Sonata in B![]() major, mvt. 2[2]

major, mvt. 2[2]

Listen to the piece, performed by harpist Kyunghee Kim-Sutre, on Spotify.

Learn about English composer Sophia Dussek (1775–1847) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Barbara Garvey Jackson, Howard Allen Craw, and Bonnie Shaljean.

Video: T62 Binary form example: Analysis of Dussek, op. 2, no. 1, mvt. 2 (8:00)

This video presents an analysis of form in Sophia Dussek’s op. 2, no. 1, Harp Sonata in B![]() major, mvt. 2 (Example 34-1). In this video, we learn that the form design of this movement is best described as continuous, simple binary, using a two-reprise form.

major, mvt. 2 (Example 34-1). In this video, we learn that the form design of this movement is best described as continuous, simple binary, using a two-reprise form.

In contrast, Example 34‑2 does not modulate and is entirely diatonic in the key of C major. Because it ends with tonic harmony in the tonic key before the point of bisection (there is an implied authentic cadence in mm. 7–8), it is a sectional form. The opening melody is restated at the end of the B section (compare the material starting at m. 1 and m. 17), creating a rounded binary form. Like most rounded binary forms, this movement is also asymmetrical to account for the additional return of the opening material. The two-reprise structure of Example 34‑2 allows listeners to perceive it in two distinct parts, in spite of the rounded asymmetrical design. Figure 34‑7 provides a diagram summarizing the formal and harmonic features of this theme.

Example 34‑2. W. A. Mozart, K. 265, Variations on “Ah, vous, dirai-je, Maman,” Theme

Listen to the piece, performed by Ronald Brautigam, on Spotify.

Learn about Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Cliff Eisen and Stanley Sadie.

Figure 34‑7. Form diagram for Example 34‑2

Video: T63 Binary form example: Analysis of Mozart, K. 265, Theme (3:53)

This video presents an analysis of the Theme from Mozart’s K. 265, Variations on “Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman” (Example 34-2). In the video, we learn that the form of this movement is best described as sectional, rounded binary, using a two-reprise form.

Example 34‑3 is an example of , which is both rounded (mm. 1–8 are restated following the bridge section) and continuous (there is an implied before the point of bisection). When a musician performs the repeats, we hear the form as represented in Figure 34‑8.

Example 34‑3. Valerie Capers, “Billie’s Song” from Portraits in Jazz

‘Billie’s Song’

‘Billie’s Song’

By Valerie Capers from ‘Portraits in Jazz’

© Oxford University Press Inc 2000, assigned to Oxford University Press 2010.

All rights reserved.

Listen to this piece, performed by pianist Edith Widayani, on Spotify.

Learn about American pianist and composer Valerie Capers (b. 1935) by reading the bio on her official website.

Figure 34‑8. Form diagram for Example 34‑3

Video: T64 Binary form example: Analysis of Valerie Capers, “Billie’s Song” (5:07)

This video presents an analysis of binary form in Valerie Capers’s “Billie’s Song,” from her 1976 collection Portraits in Jazz (Example 34-3). In the video, we identify the form as an example of 32-bar song form, which is continuous and rounded.

EXERCISE 34-1 Binary form analysis

PART A. Study and listen to Worksheet example 34‑1, and answer these questions regarding the example:

- What is the overall key of the piece?

- This piece modulates. To what key does it modulate?

- What is the relationship between the keys given in the answers to questions 1 and 2 above?

- Is the form of this piece continuous or sectional?

- There is a in this piece. In what measures does the occur? In what measures does the first of the sequence following the model occur?

- On a separate sheet of paper, neatly draw a form diagram for this piece. Include:

-

- measure numbers

- key areas (account for all modulations) shown as letters (e.g., CMA or Ami) as well as in Roman numerals (e.g., I or vi)

- uppercase letters to designate large sections

- slurs or bubbles labeled with lowercase letters to designate phrases

- cadence labels

Worksheet example 34‑1. Anon., Minuet in D minor from the Anna Magdalena Bach Notebook

Listen to this piece, performed by Daniel Wiesner, on Spotify.

PART B. Study and listen to Worksheet example 34‑2, and answer these questions regarding the example:

- What is the overall key of the piece?

- This piece modulates and features several . Complete a Roman numeral analysis beneath the staff, accounting for any modulations and .

- Is the form of this piece continuous or sectional?

- Is the form of this piece balanced binary? Why or why not?

- On a separate sheet of paper, neatly draw a form diagram for this piece. Include:

-

- measure numbers

- key areas (account for all modulations) shown as letters (e.g., CMA or Ami) as well as in Roman numerals (e.g., I or vi)

- uppercase letters to designate large sections

- slurs or bubbles labeled with lowercase letters to designate phrases

- cadence labels

Worksheet example 34‑2. George Frideric Handel, Concerto Grosso in F major, op. 3, no. 4, mvt. 4

Listen to this piece performed by the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, on Spotify.

Learn about English composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Anthony Hicks.

EXERCISE 34-2 Contextual listening with form

This excerpt is in a (binary with repeats). After listening to the audio example below several times, answer the following questions.

- Is the piece’s form continuous or sectional?

- Is the piece’s form rounded or simple?

- Is the design symmetrical or asymmetrical?

- What elements create unity between the A and B sections?

- What elements create contrast between the A and B sections?

- Who is a likely composer of this piece?

- When might this piece have been written?

Feeling ambitious? Transcribe the opening motive (played in the right hand) on a separate sheet of staff paper.

Supplemental materials for Chapter 34

- Jan LaRue, Guidelines for Style Analysis, 2nd ed., Detroit Monographs in Musicology/Studies in Music, no. 12 (Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 1992). ↵

- Example from https://www.expandingthemusictheorycanon.com/binary/ ↵

form design consisting of two large parts

musical passage that concludes with a cadence

binary form whose large sections use repeat signs

term describing pieces in binary form in which the A section can stand on its own harmonically, meaning that the A section ends with an authentic cadence in the tonic key

abbreviation for "imperfect authentic cadence," which refers to any cadence that moves from dominant function to the tonic triad in which any of the chords is inverted or uses the leading tone chord instead of V, or in which a scale degree other than 1 ("do") is in the highest part or melody with the tonic chord

abbreviation for "perfect authentic cadence," which is the most conclusive cadence type, having both of the following features: (1) the cadence uses a dominant chord in root position followed by a tonic chord in root position, and (2) the tonic triad uses scale degree 1 (“do”) in the soprano melody or main melodic part

abbreviation for "half cadence," the term referring to a cadence type that ends with a dominant chord

term describing pieces in binary form whose A section does not stand on its own harmonically, meaning the A section ends with either an open cadence in the tonic key, or any cadence in a key other than tonic

term describing pieces in binary form that do not feature material from the A section in the B section

term describing pieces in binary form in which a portion of the A section returns at the end of the B section

type of rounded binary form with an internal structure of 8 bars (A), 8 bars (A'), 8 bars (B, or bridge), 8 bars (A'')

in form design, term denoting a contrasting section; used when discussing 32-bar song form and forms in popular music

technique found in some Baroque dance movements, in which a brief portion of the end of the A section (usually stated in the key of the dominant) is restated at the end of the B section in the tonic key

term used to describe pieces in binary form in which the length of the sections is the same, or nearly the same

term used to describe pieces in binary form whose large sections are different lengths (usually the B section will be longer than the A section)

term referring to notes within a key

term referring to notes outside of a key

chords that use ninths, elevenths, or thirteenths above the root

the length of a sustained sound

speed at which a piece of music is played; often measured in beats per minute (bpm)

rate of textural change

the rate of chord change

beginning section of a piece or movement

ending section of a piece or movement

type of key relationship in which the key signatures differ only up to one sharp or flat

cadence type that ends with a dominant chord; abbreviated as "HC"

process in which a portion of music (both intervallic and rhythmic content) is successively replicated at a different pitch level

with regard to melodic sequence, the first iteration of sequential material

with regard to melodic sequence, term referring to each subsequent iteration of sequential material, following the initial model

short passage of music in a new key, longer than a tonicization but not a full modulation

process in which a secondary dominant appears, temporarily destabilizing the tonic key and resolving to a different, albeit momentary, new tonic