Main Body

16 Harmonic function and cadences

Learning goals for Chapter 16

In this chapter, we will learn:

- The three types of basic tonal function (tonic, predominant, and dominant)

- Tonal cadence types

- How to aurally identify tonal function and cadences

- How to identify tonal function and cadences in scores

Primary diatonic chords

There are three : tonic (T), predominant (P), and dominant (D). The chords built on scale degrees ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are called the , and they fill these three functions. In major keys, these chords are represented by Roman numerals I, IV, and V, or 1, 4, and 5 in the (NNS). In minor keys, the primary diatonic chords are represented by Roman numerals i, iv, and V, or NNS 6-, 2-, and 3.

are called the , and they fill these three functions. In major keys, these chords are represented by Roman numerals I, IV, and V, or 1, 4, and 5 in the (NNS). In minor keys, the primary diatonic chords are represented by Roman numerals i, iv, and V, or NNS 6-, 2-, and 3.

The most basic functional progression uses only tonic and dominant functions: I – V(7) – I (or in minor, i – V(7) – i). Using all three primary diatonic functions, the most typical functional progression in tonal music is I – IV – V(7) – I (or in minor, i – iv – V(7) – i). Many variations on this progression are possible. A seventh may be added to any chord without changing its diatonic function. In fact, the seventh of a chord sometimes enhances the chord’s function. Adding a seventh to the dominant triad, for example, strengthens its pull to tonic resolution since its third (the leading tone, “ti”) and seventh (scale degree ![]() , “fa”) form a tritone that requires resolution to the root (tonic, “do”) and third (scale degree

, “fa”) form a tritone that requires resolution to the root (tonic, “do”) and third (scale degree ![]() , “mi” or “me”) of the tonic triad.

, “mi” or “me”) of the tonic triad.

EXERCISE 16-1 Harmonic function in context

Name the minor key given the key signature, and spell the tonic triad and dominant seventh chord on a separate sheet of staff paper or below. Select the right arrow over the image to view the answer. Then listen to the repeating basic functional progression in Worksheet example 16-1.

Worksheet example 16‑1. Marc Anthony, “I Need to Know,” 0:00–0:34

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about American Latino singer, songwriter, and actor Marc Anthony (b. 1968) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Frances R. Aparicio.

Name the major key given the key signature, and spell the primary diatonic triads (I, IV, and V) in that key on a separate sheet of staff paper or below. Select the right arrow over the image to view the answer. Then listen to these chords in Worksheet examples 16‑2 and 16‑3.

Worksheet example 16‑2. R.E.M., “Stand,” 0:09–0:27

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about American rock band R.E.M. by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Fred Everett Maus.

Worksheet example 16‑3. George Harrison, “Got My Mind Set on You,” 0:19–0:32

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about English musician and former Beatle George Harrison (1943–2001) by reading this Britannica article, revised and updated by Alicja Zelazko.

Name the major key given the key signature, and spell the primary diatonic triads (I, IV, and V) in that key, featured in Worksheet examples 16-4, 16-5, and 16-6. Select the right arrow over the image to view the answer. Worksheet examples 16-4 and 16-5 use I, IV, and V in succession, whereas Worksheet example 16-6 uses the chords in the following progression: I – V – IV – V.

Worksheet example 16‑4. The Cat Empire, “One Four Five,” 0:45–1:01

Worksheet example 16‑5. Eric Clapton, “Lay Down Sally,” 0:38–0:58

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about English blues and rock guitarist Eric Clapton (b. 1945) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Susan Fast.

Worksheet example 16‑6. Hanson, “MMMBop,” 0:55–1:15

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about American pop band Hanson by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Jessica L. Brown.

Name the major key given the key signature, and spell the primary diatonic triads (I, IV, and V) in that key, featured in The Walkmen’s “Heartbreaker” (Worksheet example 16-7). Select the right arrow over the image to view the answer.

Worksheet example 16‑7. The Walkmen, “Heartbreaker,” 0:00–0:16

Name the major key given the key signature, and spell the primary diatonic triads (I, IV, and V) in that key, featured in Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” (Worksheet example 16‑8). Select the right arrow over the image to view the answer. This example uses the following progression with the primary diatonic chords: I – IV – I – V – I – IV – I – V – I.

Worksheet example 16‑8. Dolly Parton, “9 to 5,” 0:00–0:29

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about American country singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Dolly Parton (b. 1946) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Jada Watson.

Video: T33 Harmonic function (8:56)

This video explores the three primary diatonic functions in tonal music: , , and . Musical examples include songs by Marc Anthony, R.E.M., George Harrison, and The Cat Empire.

Harmonic dictation

One way to get better at identifying harmonic function by ear is to practice dictation short harmonic progressions that use only primary diatonic chords in root position. To this end, Appendix E, nos 1–6 and 8–10, contains dictations with these chords. To practice this skill, listen to each short progression up to four times with the goals of notating the soprano and bass voices, providing Roman numerals beneath the staff, and identifying the cadence. Only notes belonging to the chords are used, so thinking about how to spell the I, IV, and V or V7 chords ahead of time may be useful to eliminate chord choices that do not feature the notes contained in a given soprano or bass voice.

Secondary diatonic chords

The remaining diatonic triads and seventh chords (built on scale degrees ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() ) are called and generally serve one of the three primary functions (tonic, predominant, or dominant).

) are called and generally serve one of the three primary functions (tonic, predominant, or dominant).

The chord assumes predominant function, and it may substitute for the subdominant chord. The chord, having tonic function, usually substitutes for the tonic chord. One common use of the submediant triad occurs in the , where it surprises or “deceives” the listener who expects to hear tonic, but instead hears submediant, after a V or V7 chord. The chord functions dominantly and substitutes for the dominant chord. Figure 16‑1 summarizes the function and quality for the most common primary and secondary diatonic chords.

Figure 16‑1. Diatonic chord function chart

The chord, used rarely, is the only chord that resists clear classification within the system of three diatonic functions addressed here. Sometimes it extends tonic function, and other times it functions dominantly. There are other times when it appears as part of a harmonic sequence, negating any immediate T, P, or D function. We will study the unique uses of the mediant chord in Chapter 18.

Cadences

William S. Rockstro and others define a as

“the conclusion to a phrase, movement or piece based on a recognizable melodic formula, harmonic progression or dissonance resolution; [or] the formula on which such a conclusion is based.”[1]

This chapter defines cadences by the type of chords that appear at the end of a phrase. Figure 16‑2 summarizes the types of cadences used in European Baroque, Classical, and Romantic music. It is also possible to hear and identify these cadence types in other tonal genres.

Figure 16‑2. Cadence types

There are four primary types of cadences: (dominant function to tonic triad), (subdominant chord to tonic chord), (dominant function to non-tonic triad with tonic function), and (predominant or tonic function to dominant chord). Each has its own particular harmonic structure, as described in Figure 16‑2 above.

are considered the most conclusive and stable of all cadences, signaling harmonic closure. They are often used to end large sections and entire pieces. There are two types of authentic cadences: the and the . The (or PAC) has two strict requirements: (1) it must use a dominant chord in root position followed by a tonic chord in root position, and (2) the tonic triad must be harmonized with scale degree ![]() (“do”) in the soprano melody or main melodic part. Any other cadence that moves from dominant function to the tonic triad is considered an (or IAC).

(“do”) in the soprano melody or main melodic part. Any other cadence that moves from dominant function to the tonic triad is considered an (or IAC).

The (or PC) also signals closure, but it is not considered quite as strong as an authentic cadence, since there is no dominant function to set up the resolution to tonic. Still, it is a conclusive cadence, and it is sometimes referred to as the “Amen” cadence because it is heard at the end of some Christian hymns.

(or DC) surprise or “deceive” the listener who expects to hear tonic, but instead hears a chord substituting for tonic, after the V or V7 chord. Usually, the tonic substitute is the submediant triad, but occasionally it may be a different chord altogether. Since they do not conclude with the tonic triad, deceptive cadences are more open and less conclusive than authentic and plagal cadences.

(or HC) are the most open type of cadence. Because they end with an unresolved dominant chord, they beg for resolution to come in the next phrase or section. There is a special type of half cadence that can occur in minor keys, when iv6 precedes the dominant chord, called the (or Phrygian HC).

Video: T34 Cadences in context (15:12)

This video introduces the different cadence types (PAC, IAC, PC, DC, and HC) and explores them in music by L. Viola Kinney, Florence Price, Paul Simon, Styx, Mozart, and the Beatles. The same music is presented in Examples 16-1 through 16-6.

Cadences in context

Our first contextual example shows a (PAC) in a piece by L. Viola Kinney. See the last two measures in Example 16‑1. We can tell that this example is a perfect authentic cadence because it involves dominant to tonic function, both the dominant seventh and the tonic chord are in root position, and the melody ends on tonic (G).

Example 16‑1. L. Viola Kinney, “Mother’s Sacrifice,” mm. 50–57

Example 16‑2 shows an example of an (IAC) at the end of the excerpt. Like the PAC, it moves from dominant function to tonic. Both chords are in root position, but the melody ends on scale degree ![]() (E), rather than tonic (C). The melody ending on a note other than tonic is what makes this cadence an IAC rather than a PAC.

(E), rather than tonic (C). The melody ending on a note other than tonic is what makes this cadence an IAC rather than a PAC.

Example 16‑2. Florence Price, “Night,” mm. 20–27

Listen to the full track, performed by soprano Icy Rene Simpson, on Spotify.

Learn about African-American composer Florence Price (1887–1953) by reading this Oxford Music Online article written by Rae Linda Brown.

The excerpt in Example 16‑3 presents a plagal cadence, moving from the predominant chord to tonic.

Example 16‑3. Paul Simon, “A Church Is Burning,” 0:00–0:18

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about American singer-songwriter Paul Simon (b. 1941) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by David Brackett

In Example 16‑4, listen for the words “hands of time.” You will hear the VI chord substituting for tonic to create a deceptive cadence.

Example 16‑4. Styx, “The Best of Times,” 0:00–0:21

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about 20th-century American rock band Styx by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Michael Ethen.

Occasionally, chords other than the submediant are used to substitute for tonic in a deceptive cadence. An exciting chromatic deceptive cadence occurs in the Kyrie movement of Mozart’s Requiem, as shown in Example 16-5. Thinking in the key of D minor, m. 97 ends with a dominant seventh chord, leading many listeners to expect a tonic triad in the following measure. Instead, Mozart uses a G![]() fully diminished chord in m. 98, thus creating an unexpected deceptive cadence.

fully diminished chord in m. 98, thus creating an unexpected deceptive cadence.

Example 16‑5. W. A. Mozart, Kyrie from Requiem, K. 626, mm. 96–100

Listen to the full track, performed by the Dunedin Consort, on Spotify.

Learn about Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Cliff Eisen and Stanley Sadie.

Unlike authentic and plagal cadences, which end with tonic and thus sound more tonally conclusive, the most open and inconclusive cadence is the , ending on the dominant chord, which we can hear in context at the end of the Beatles’ “For No One” in Example 16‑6.

Example 16‑6. The Beatles, “For No One,” 1:28–1:56

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about 20th-century English rock band the Beatles and their music by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Walter Everett.

Self-check quiz on cadence types

EXERCISE 16-2 Analysis with I, IV, and V(7)

Study and listen to the following excerpts. Then provide labels for the chords with the appropriate Roman numeral and figured bass symbols. In your analysis, disregard non-chord tones, which are placed in parentheses. Also identify the type of texture and cadences where indicated.

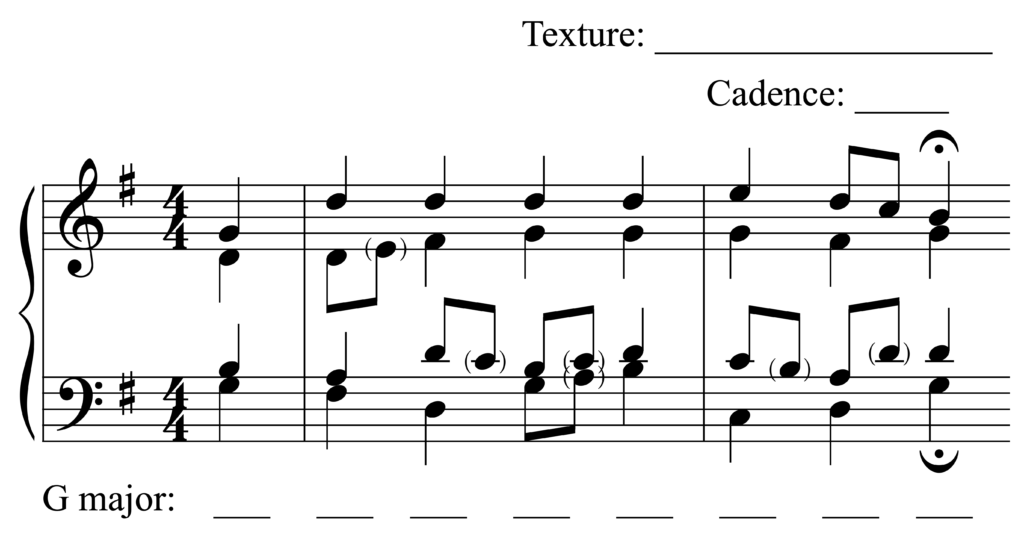

Worksheet example 16‑9. J. S. Bach, “Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich,” mm. 1–2

Listen to the full track, performed by the King’s College Choir, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Christoph Wolff and Walter Emery.

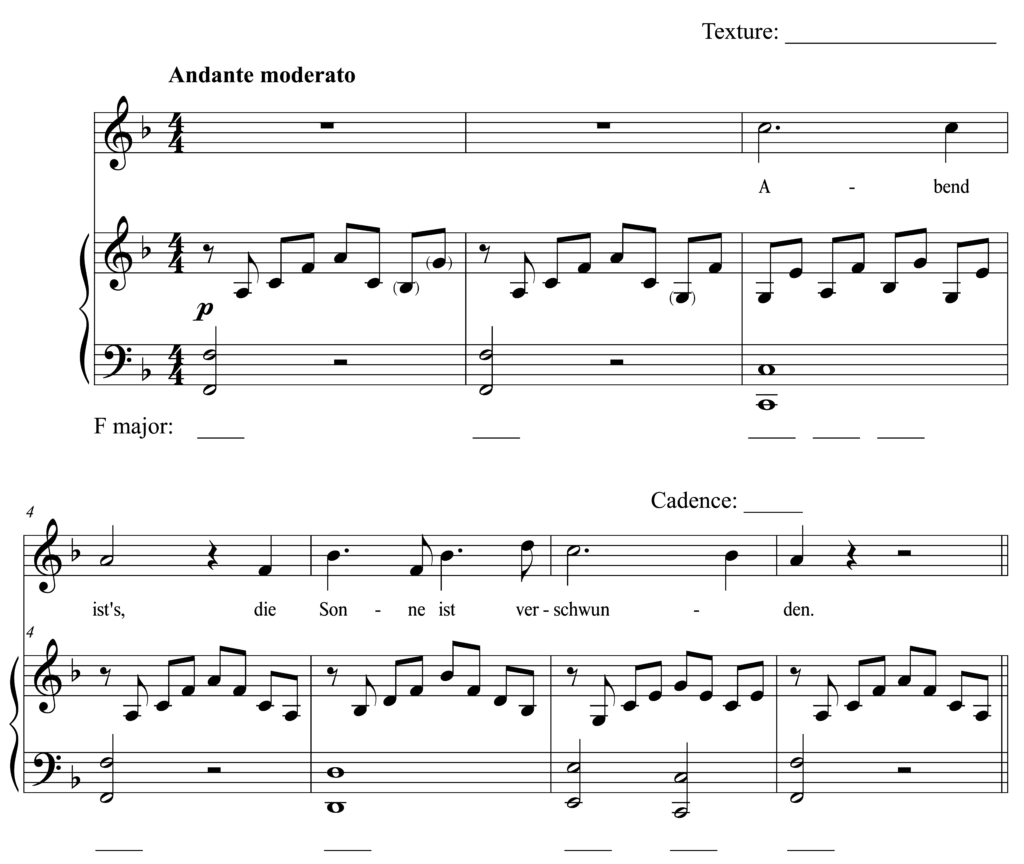

Worksheet example 16‑10. W. A. Mozart, Abendempfindung, K. 523, mm. 1–7

Listen to the full track, performed by Elly Ameling and Dalton Baldwin, on Spotify.

Read an English translation of the song text on lieder.net.

Learn about Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Cliff Eisen and Stanley Sadie.

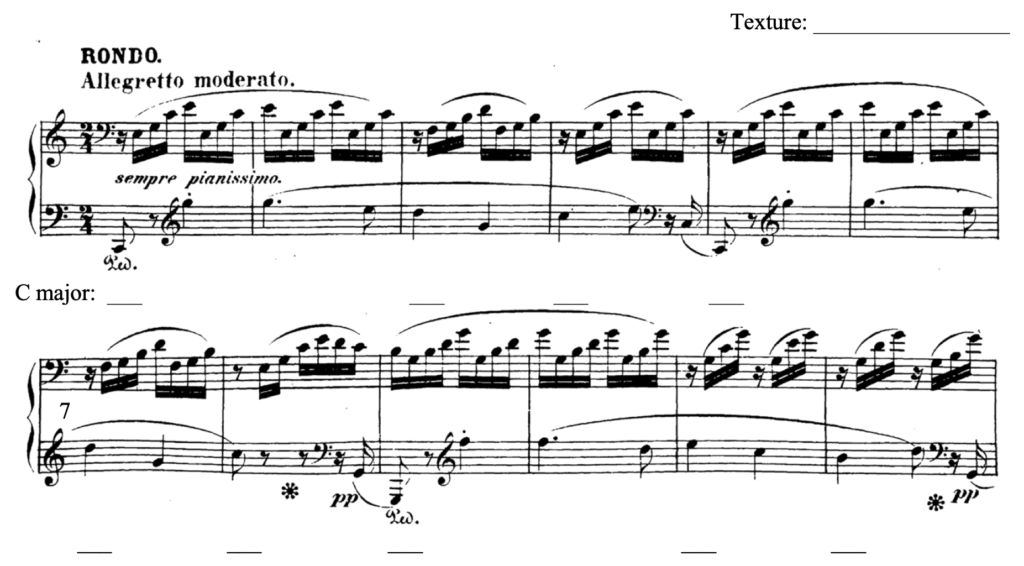

Note: In most of Worksheet example 16-11, the hands are crossed, so the right-hand part is lower than the left-hand part when this occurs. (Note the clefs used for each hand.) This means that some of the bass notes will be found in the upper staff.

Worksheet example 16‑11. Ludwig van Beethoven, Piano Sonata no. 21, op. 53, “Waldstein,” mvt. 3, mm. 1–12

Listen to the full track, performed by pianist Richard Goode, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Joseph Kerman and others.

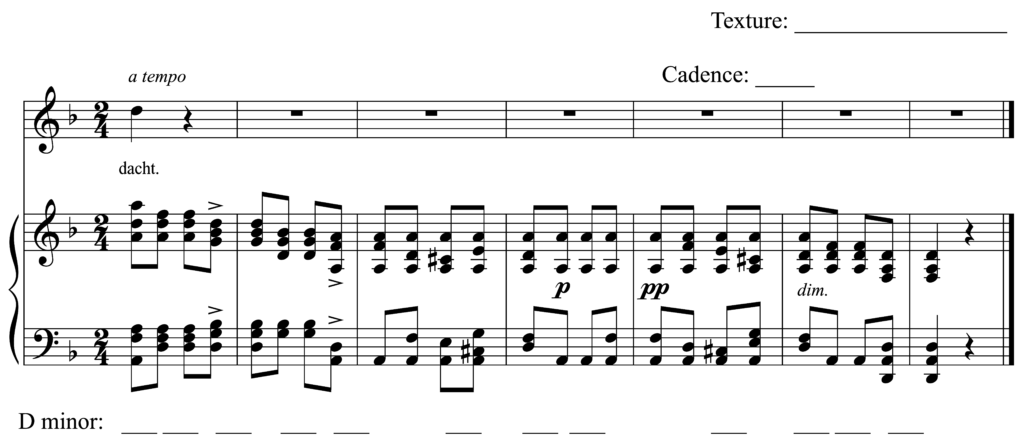

Worksheet example 16‑12. Franz Schubert, “Gute Nacht,” from Winterreise, mm. 99–105

Listen to the full track, performed by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, on Spotify.

Learn about Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Maurice J. E. Brown and others.

EXERCISE 16-3 Analysis of J. S. Bach’s “Wachet Auf”

After listening to this piece and studying the score, identify the chords at each cadence with Roman numerals and figured bass symbols. Once you have determined those labels, identify the appropriate cadence types in the boxes above the staff. Most of this piece is in E![]() major, but there is a section that modulates to the key of B

major, but there is a section that modulates to the key of B![]() major. Key changes are indicated when it is relevant to your analysis of the cadences.

major. Key changes are indicated when it is relevant to your analysis of the cadences.

Worksheet example 16‑13. J. S. Bach, Chorale 329. “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme”

Listen to this piece, performed by organist Claudio Colombo, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Christoph Wolff and Walter Emery.

Supplemental resources for Chapter 16

- William S. Rockstro, et al., “Cadence,” in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/04523. ↵

the three typical chord functions in tonal music, which are tonic (T), representing closure and stability; predominant (P), signaling a shift prior to dominant function; and dominant (D), representing tension and instability

the chords built on scale degrees 1, 4, and 5

system for labeling chord progressions, using Arabic numbers and symbols to show chord function and alterations

the most stable tonal function of repose, resolution, or conclusion, exemplified by the triad built on scale degree 1

a tonal function that typically precedes dominant function; chords with predominant function include the subdominant triad and chords built on scale degree 2

the most unstable tonal function characterized by tension, setting up a listener’s expectation to hear tonic as a resolution; chords with dominant function include the dominant triad, dominant seventh, and chords built on the leading tone

chords built on scale degrees 2, 3, 6, and 7

scale degree 2, or the chord built on scale degree 2

scale degree 6, or the chord built on scale degree 6

cadence which consists of two chords: dominant (V or V7) to a chord other than tonic, usually the submediant triad; abbreviated as "DC"

scale degree 7 in any major, harmonic minor, or ascending melodic minor scale; this scale degree is always a half step below tonic

scale degree 3

the end of a phrase, defined by its harmonic motion into one of the following categories: authentic cadence (V - I), plagal cadence (IV - I), half cadence (end on V), or deceptive cadence (V - vi)

cadence type that features dominant to tonic

cadence type that features subdominant to tonic; abbreviated as "PC"

cadence type that ends with a dominant chord; abbreviated as "HC"

the most conclusive cadence type, having both of the following features: (1) the cadence uses a dominant chord in root position followed by a tonic chord in root position, and (2) the tonic triad uses scale degree 1 (“do”) in the soprano melody or main melodic part; abbreviated as "PAC"

any cadence that moves from dominant function to the tonic triad in which any of the chords is inverted or uses the leading tone chord instead of V, or in which a scale degree other than 1 ("do") is in the highest part or melody with the tonic chord; abbreviated as "IAC"

special type of half cadence that can occur in minor keys, which features iv6 - V