Main Body

17 Melody

Learning goals for Chapter 17

In this chapter, we will learn:

- Features of effective tonal melodies

- How to construct a tonal melody

- How harmonic implication can enhance a tonal melody

- A procedure for sight singing melodies

Features of tonal melodies

Although there are many different tonal styles, occurring in different cultural and geographic contexts and spanning centuries, we can identify some features that the most effective tonal melodies have in common. For each of the following musical examples, pay attention to the following:

- What scale degree does the melody start on?

- What scale degree does the melody end on?

- For melodies in a minor key, what scale types are used most often?

- What kind of motion is used most often—stepwise or leaps?

- What sorts of contours are used?

Example 17‑1, in the key of E![]() major, begins and ends on the tonic scale degree. The final tonic scale degree arrives on a downbeat. The melody features mostly stepwise motion with a few small leaps of thirds. In m. 4, the melody outlines the notes of an A

major, begins and ends on the tonic scale degree. The final tonic scale degree arrives on a downbeat. The melody features mostly stepwise motion with a few small leaps of thirds. In m. 4, the melody outlines the notes of an A![]() major triad, accounting for a leap of a third followed by a fourth. All notes involved in the leaping motion are consonant with the harmony (A

major triad, accounting for a leap of a third followed by a fourth. All notes involved in the leaping motion are consonant with the harmony (A![]() major).

major).

Example 17‑1. Transcription of Björk, “Who Is It,” verse 1, 0:20–0:52

Example 17‑2, in E minor, similarly begins and ends on the tonic scale degree, again with the ending placed on a downbeat. This melody features mostly stepwise motion, with some implied at the end of each measure. At the cadence, the melody features D![]() , the leading tone of the key, implying the harmonic minor scale.

, the leading tone of the key, implying the harmonic minor scale.

Example 17‑2. J. S. Bach, Flute Sonata in E Minor, Allegro, mm. 1–4

Listen to the full track, performed by flutist William Bennett, on YouTube.

Learn about German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Christoph Wolff and Walter Emery.

Example 17‑3 appears in C major, and like the previous examples, it begins and ends on tonic. In an otherwise mostly stepwise melody, its only leaps are to , meaning notes that are consonant with the harmony.

Example 17‑3. Transcription of Lady Gaga, “Bad Romance,” 0:00–0:17

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about American pop artist Lady Gaga (b. 1986) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Meredith Evans.

Example 17‑4 features a melody in F![]() minor, and like Example 17‑2, it uses the at cadences. Here, the cadences are in mm. 3–4 (using ) and mm. 7–8 (using ). Like the previous examples, the melody is mostly stepwise, and its only leaps outline chord tones.

minor, and like Example 17‑2, it uses the at cadences. Here, the cadences are in mm. 3–4 (using ) and mm. 7–8 (using ). Like the previous examples, the melody is mostly stepwise, and its only leaps outline chord tones.

Example 17‑4. Trad., “Greensleeves,” sung by Jessye Norman

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about American soprano Jessye Norman (1945–2019) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Martin Bernheimer, Alan Blythe, and Karen M. Bryan.

Example 17‑5, in the key of B![]() major, features more leaping motion than the previous examples, and most leaps outline important chord tones. This melody also begins and ends on the tonic scale degree. The contour of this melody is more dynamic and wider ranging than in the previous examples due to its greater use of leaps.

major, features more leaping motion than the previous examples, and most leaps outline important chord tones. This melody also begins and ends on the tonic scale degree. The contour of this melody is more dynamic and wider ranging than in the previous examples due to its greater use of leaps.

Example 17‑5. Transcription of Beyoncé, “Irreplaceable,” 0:55–1:08, by Robert Hutchinson[1]

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about American singer Beyoncé Knowles (b. 1981) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Mark Anthony Neal.

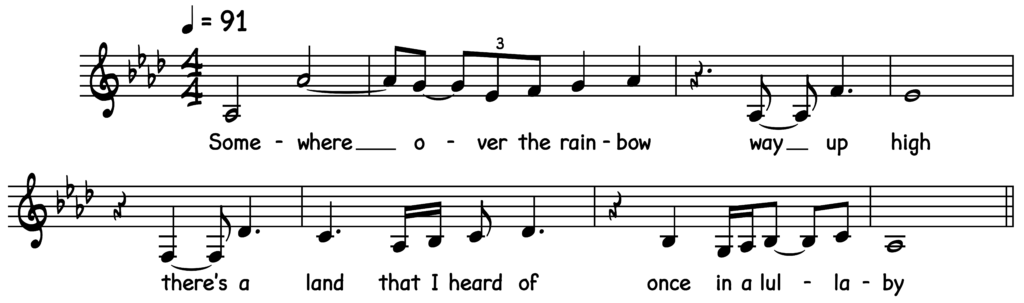

Like the previous examples, Example 17‑6 also begins and ends on the tonic scale degree (A![]() ), and the final note appears on a downbeat. This melody features several wide intervals for expressive purposes, beginning with an ascending octave and using ascending sixths in mm. 3 and 5. These leaps outline chord tones, but their wide nature makes the melody less easy to sing than a mostly stepwise melody. The large leaps are marked, creating dramatic effect suitable for the song’s context in The Wizard of Oz.

), and the final note appears on a downbeat. This melody features several wide intervals for expressive purposes, beginning with an ascending octave and using ascending sixths in mm. 3 and 5. These leaps outline chord tones, but their wide nature makes the melody less easy to sing than a mostly stepwise melody. The large leaps are marked, creating dramatic effect suitable for the song’s context in The Wizard of Oz.

Example 17‑6. Transcription of Judy Garland singing Harold Arlen, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” mm. 1–8

Listen to the full track, performed by Judy Garland, on Spotify.

Learn more about American composer Harold Arlen (1905–1986) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Larry Stempel.

Example 17‑7, in D major, emphasizes the tonic scale degree, and like many of the previous examples, it begins and ends on tonic, with the ending placed on a downbeat. This melody features stepwise motion primarily, and its only leaps outline chord tones. For example, mm. 9, 11, and 17 feature a downward arpeggiation of the notes belonging to the tonic triad. In addition, the melody’s contour is fairly static with some instances of downward motion, which contrast the peak on A4 on the first syllable of the word “shouting.”

Example 17‑7. Transcription of Radiohead, “Stop Whispering,” 0:15–1:03

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about English rock band Radiohead by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Christopher Doll.

Example 17‑8, in A major, begins and ends on the tonic scale degree, again with the ending placed on the downbeat. The melody features mostly stepwise motion and leaps only to chord tones.

Example 17‑8. W. A. Mozart, “Là ci darem la mano,” mm. 1–8, from Don Giovanni

Listen to the full track, performed by Austrian lyric baritone Eberhard Wächter, on Spotify.

Read an English translation of the libretto, translated by Jennifer Rushworth, from the Oxford International Song Festival website.

Learn more about Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Cliff Eisen and Stanley Sadie.

Example 17‑9 appears in G minor. It begins on the dominant scale degree (D) and ends on tonic (G) placed on the downbeat. This melody features a fairly narrow range, spanning just a perfect fifth from G4 to D5. Since it doesn’t feature scale degrees ![]() or

or ![]() , there is no possibility of using the harmonic or melodic forms of minor. Its primary motion is stepwise, and the leaps occur only to consonant chord tones.

, there is no possibility of using the harmonic or melodic forms of minor. Its primary motion is stepwise, and the leaps occur only to consonant chord tones.

Example 17‑9. Isabella Colbran, “Quel ruscelletto che l’onde chiare,” mm. 5–12

Listen to the full track, performed by Maria Chiara Pizzoli, on Spotify.

Learn more about Spanish soprano and composer Isabella Colbran (1785–1845) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Elizabeth Forbes.

In Example 17‑10, in the key of C major, the melody begins on scale-degree ![]() (E) and ends on tonic (C), placed on a downbeat. The contour of the melody as a whole peaks at A4 and concludes with a descent, mostly stepwise, to C4.

(E) and ends on tonic (C), placed on a downbeat. The contour of the melody as a whole peaks at A4 and concludes with a descent, mostly stepwise, to C4.

Example 17‑10. Transcription of Leonard Cohen, “Hallelujah,” recording by Jeff Buckley, 1:26–1:43

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about Canadian songwriter Leonard Cohen (1934–2016) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Mark Samples.

Learn more about American singer and guitarist Jeff Buckley (1966–1997) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Mark Samples.

Example 17‑11 is in B![]() major, and it begins and ends on tonic (B

major, and it begins and ends on tonic (B![]() ). (The overall key of the full recording shifts between G minor and B

). (The overall key of the full recording shifts between G minor and B![]() major.) The melody is mostly stepwise, with a leap to the apex of the melody on G4, creating a contour that is first upward, then downward.

major.) The melody is mostly stepwise, with a leap to the apex of the melody on G4, creating a contour that is first upward, then downward.

Example 17‑11. Transcription of The Cliks, “Still,” 1:39–1:53

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about Canadian indie rock band The Cliks at the band’s website.

Example 17‑12, in D major, begins on the mediant scale degree (F![]() ) and ends on tonic (D). A half cadence is implied in m. 8, in tandem with scale degree

) and ends on tonic (D). A half cadence is implied in m. 8, in tandem with scale degree ![]() (E) in the melody. As with many of the previous examples, this melody features mostly stepwise motion with several small leaps (thirds).

(E) in the melody. As with many of the previous examples, this melody features mostly stepwise motion with several small leaps (thirds).

Example 17‑12. Franz Joseph Haydn, Symphony no. 104, mvt. 1, Allegro, mm. 1–16, melody

Listen to the full track, performed by the Royal Concertgebouw and conducted by Sir Colin Davis, on Spotify.

Learn more about Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Georg Feder and James Webster.

Example 17‑13 emphasizes chord tones (notes belonging to the harmony), especially on downbeats. This melody uses expressive up and down contours, as well as mostly stepwise motion.

Example 17‑13. Transcription of Elliott Smith, “Twilight,” 0:02–0:29

Example 17‑14, in G![]() minor, begins on tonic (G

minor, begins on tonic (G![]() ) and ends on scale degree

) and ends on scale degree ![]() (B). It features mostly stepwise motion and descending contours. The melody uses the natural minor scale: it does not use the (F𝄪), but rather the scale degree (F

(B). It features mostly stepwise motion and descending contours. The melody uses the natural minor scale: it does not use the (F𝄪), but rather the scale degree (F![]() ).

).

Example 17‑14. Transcription of Justin Timberlake, “Cry Me a River,” 1:43–2:09

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn more about American pop and R&B singer Justin Timberlake (b. 1981) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Miles White.

In sum, these examples, spanning a fairly wide range of tonal styles, generally share the following characteristics:

- They start on tonic or another scale degree in the tonic chord (

,

,  , or

, or  ).

). - They often end on tonic, usually placed on the downbeat.

- They often end with stepwise motion toward tonic (

–

– or

or  –

– ).

). - When in a minor key, they often use melodic or harmonic minor, as in Example 17‑2 and Example 17‑4.

- They use mostly stepwise motion or, a mix of stepwise motion and small leaps.

- Most leaps outline a chord (ex: leaps among

,

,  , and

, and  outlining tonic), as in Example 17‑5 (the opening three notes) and Example 17‑7 (see mm. 9, 11, and 17).

outlining tonic), as in Example 17‑5 (the opening three notes) and Example 17‑7 (see mm. 9, 11, and 17). - Large leaps are used sparingly, only for dramatic effect, as in the opening octave leap in Example 17‑6.

- Contours vary, but there is usually a melodic peak.

Finally, Kris Shaffer and Mark Gotham summarize some general principles associated with tonal melodies, drawing from David Huron’s research in cognition and perception (2006). They include:

Pitch proximity: The tendency for melodies to progress by steps more than leaps and by small leaps more than large leaps. An expression of smoothness and melodic integrity.

Step declination: The tendency for melodies to move by descending step more than ascending. Possibly an expression of goal-oriented motion, as we tend to perceive a move down as a decrease in energy (movement toward a state of rest).

Step inertia: The tendency for melodies to change direction less frequently than they continue in the same direction. (That is, the majority of melodic progressions are in the same direction as the previous one.) An expression of smoothness and, at times, goal-oriented motion.

Melodic regression: The tendency for melodic notes in extreme registers to progress back toward the middle. An expression of motion toward a position of rest (with non-extreme notes representing “rest”). Also an expression simply of the statistical distribution of notes in a melody: the higher a note is, the more notes there are below it for a composer to choose from, and the fewer notes there are above it.

Melodic arch: The tendency for melodies to ascend in the first half of a phrase, reach a climax, and descend in the second half. An expression of goal orientation and the rest–motion–rest pattern. Also a combination of the above rules in the context of a musical phrase.[2]

Writing tonal melodies with strong harmonic implication

In addition to the general melodic characteristics described above, when writing a tonal melody, you should also think about its harmonic implications. Here are some guidelines for constructing a tonal, diatonic melody with a compelling harmonic implication:

- Write using a major scale, or if in minor, use the harmonic or melodic minor scale.

- Avoid using the natural minor scale or modal scales.

- Begin and end on tonic.

- Use stepwise motion at the ends of phrases (e.g., use re–do or ti–do). This will generally harmonize nicely with V – I.

- Place the final note of the melody on the downbeat of the measure.

- Use do (

), mi/me (

), mi/me ( ), and sol (

), and sol ( ) as “anchors” to ground your melody tonally. These pitches harmonize nicely with the tonic chord, which will give your melody grounding.

) as “anchors” to ground your melody tonally. These pitches harmonize nicely with the tonic chord, which will give your melody grounding.

Another way to approach melody writing is to start with a chord progression you like, decide upon a regular harmonic rhythm (e.g., one chord per bar), and construct a melody that emphasizes the chord tones of the chords in your progression by placing them on strong beats and longer durations. Here is a brief example:

Say you like the progression I – IV – V – I and want to write a melody in D major that implies this progression.

First, you would spell the notes in each chord:

I = D F![]() A

A

IV = G B D

V = A C![]() E

E

Second, you would format a staff with a clef, key signature, and time signature, and place Roman numerals and/or chord symbols to remind yourself of the chosen progression, as shown in Example 17‑15.

Third, now for the fun part! Experiment with emphasizing the notes of each chord, combining the principles we are learning about. Example 17‑16 shows three possible solutions using this method (note that non-chord tones are shown in parentheses). Try playing and/or singing these in solfege. For an added bonus, try playing the chords on guitar or piano while you sing the melody to hear the harmonic implication.

EXERCISE 17-1 Writing a melody

The purpose of this assignment is for you to write an original tonal melody using the guidelines described in this chapter. Using a piece of staff paper or notation program, please do the following:

Step 1. Choose a clef, key, and meter.

Step 2. If in major, use the I – IV – V – I progression. If in minor, use the i – iv – V – i progression.

Step 3. Construct your melody by emphasizing the chord tones of the progression above. Strive to use chord tones on strong beats, and do your best to follow the guidelines we have studied. Begin and end on tonic.

Step 4. Before submitting your work, double check to make sure:

- there are the correct number of beats per bar

- beaming reflects the beat level

- the notes placed in metrically strong positions belong in the chord

Sight singing tonal melodies

Once you have mastered singing pitch patterns in major and minor keys, the next step is to begin singing melodies at sight. The skills involved include:

- Identifying the key and meter type

- Reading rhythm correctly on a neutral syllable

- Converting notes in staff notation to solfege syllables corresponding with the key

- Singing the notes using solfege

- Combining all skills to sing the notes, in rhythm, correctly and fluently

Students often find it helpful to conduct to embody the meter and help ground the sight singing rhythmically and metrically. Others find it helpful to use Curwen hand signs to embody the contour and help ground the sight singing in terms of pitch accuracy.

Video: S12 Intro to sight singing melodies (8:35)

This video walks you through the process of how to convert notation into sound by sight singing melodies, using a four-step process: (1) identify key and tonic, (2) identify meter and conducting pattern, (3) read the rhythm of the melody on solfege syllables while conducting, and (4) establish the key and sing the melody in solfege, with accurate rhythm and pitch.

Melodic dictation

Once you feel comfortable identifying short tonal pitch patterns by ear, you may find it useful to practice notating melodies. To this end, Appendix D contains dictations for practice. Nos. 1–20 progress in difficulty and use a succession of pitch patterns introduced in Chapter 3 (major scales) and Chapter 6 (minor scales).

Supplemental resources for Chapter 17

- Robert Hutchinson, Music Theory for the 21st-Century Classroom, Figure 11.4.3, https://musictheory.pugetsound.edu/mt21c/PhraseSection.html. Accessed September 29, 2023. Used with permission of the author. ↵

- Kris Shaffer and Mark Gotham, “Introduction to Species Counterpoint,” Open Music Theory, https://viva.pressbooks.pub/openmusictheory/chapter/species-counterpoint/, accessed January 4, 2023. ↵

single-line (monophonic) melody that implies more than one voice, usually through wide leaps

notes belonging in a chord; e.g., the chord tones in a major triad are C, E, and G

scale degree 7 in any major, harmonic minor, or ascending melodic minor scale; this scale degree is always a half step below tonic

scale that features the following interval pattern: whole - half - whole - whole - half - A2 - half

scale that has the following interval pattern: ascending whole - half - whole - whole - whole - whole - half; descending whole - whole - half - whole - whole - half - whole; resembles the parallel major when ascending, except for scale degree 3, and resembles natural minor in its descending form

the scale degree a whole step below tonic, sung as "te" in moveable-do solfege, and featured in the natural minor scale and the descending melodic minor scale