Main Body

31 Secondary dominants

Learning goals for Chapter 31

In this chapter, we will learn:

- What are

- How to spell secondary dominants

- How to identify secondary dominants in musical contexts

- Strategies for listening to secondary dominants, focused on tendency tones

- How to connect secondary dominants to their chords of resolution in four voices

Secondary dominants

Similar to chords, chords—that is, chords that have one or more notes outside of the tonic key—have specific tonal functions. The most commonly occurring type of chromatic chord is the , which refers to any chord that temporarily functions as a dominant to a diatonic major or minor chord that is not tonic. Secondary dominants result in a process called . We consider a chord to be “tonicized” when its secondary dominant appears, temporarily destabilizing the tonic key and giving way to a different, albeit momentary, new tonic.

Only major triads and major-minor (MAmi7) seventh chords can function as secondary dominants. Both triads and seventh chords used as secondary dominants may be , meaning the fifth may be omitted. But even when this happens, the quality is still always either a major triad or a major-minor seventh.

Fun Fact: V7/III in minor keys is not a chromatic chord; all of its notes fit within the diatonic minor key.

Another Fun Fact: Diminished triads cannot be tonicized since tonic chords are never diminished. This means that the leading tone triad (viio) and the supertonic triad (iio) in minor keys cannot be tonicized.

Secondary dominants in context

The following examples show secondary dominants in a variety of music contexts.

In Example 31‑1, the second-to-last chord is the secondary dominant, in this case tonicizing dominant, G. The secondary dominant has one chromatic note—F![]() —outside of the tonic key of C. Because the chord has a raised third and proceeds immediately to G, we interpret the D chord not as the supertonic triad of C major, but as the dominant of the G chord to which it resolves. Since D is the V chord in the key of G, and G is V in the overall key of C, we call this “V of V,” written in Roman numeral analysis as “V/V.”

—outside of the tonic key of C. Because the chord has a raised third and proceeds immediately to G, we interpret the D chord not as the supertonic triad of C major, but as the dominant of the G chord to which it resolves. Since D is the V chord in the key of G, and G is V in the overall key of C, we call this “V of V,” written in Roman numeral analysis as “V/V.”

Example 31‑1. Franz Joseph Haydn, Symphony no. 94, mvt. 2, mm. 1–8[1]

Listen to the full track, performed by Academy of Ancient Music, conducted by Christopher Hogwood, on Spotify.

Learn about Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Georg Feder and James Webster.

Video: T53 Intro to secondary dominants (7:55)

This video introduces the concept of secondary dominants and shows its appearance in the second movement from Haydn’s Symphony no. 94 (Example 31‑1).

Now let’s take a look at Example 31-2, which is more complex. The tonic key is also C major here, but notice that even in just the first few measures, there are multiple chromatic chords. At first glance, you might think the opening chord is tonic—the root is C, and we have a stack of thirds built on tonic. However, if you take a closer look, you will see the chord is not a tonic triad, but rather a MAmi7 chord (C-E-G-B![]() ), and it is, in fact, chromatic, since the chordal seventh is B

), and it is, in fact, chromatic, since the chordal seventh is B![]() , not B

, not B![]() . This makes it a secondary dominant tonicizing the IV chord: V7/IV.

. This makes it a secondary dominant tonicizing the IV chord: V7/IV.

In measure 2, we get the true dominant of the key (G7), but it resolves deceptively not to tonic, but rather to the submediant (A minor). Measure 3 presents us with another chromatic chord—recognize its similarity to the secondary dominant in Example 31‑1? This is V7/V, now D7 (D-F![]() -A-C) instead of D, tonicizing V (G), which appears in the following measure. What an interesting way to begin a symphony—delaying the appearance of the tonic chord until later.

-A-C) instead of D, tonicizing V (G), which appears in the following measure. What an interesting way to begin a symphony—delaying the appearance of the tonic chord until later.

Example 31‑2. Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, mvt. 1, mm. 1–4[2]

Listen to the full track, performed by the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, conducted by George Szell, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Joseph Kerman and others.

Video: T54 Secondary dominants in Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1, mvt. 1 (10:41)

This video walks you through a harmonic analysis of the first four measures of the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1 (Example 31‑2), which interestingly has no tonic chords until later in the movement. This passage features two different secondary dominants, as well as a deceptive resolution of a primary dominant seventh.

Example 31‑3 uses the V7/IV in , so the chordal seventh (F![]() ) resolves down by step in the bass, and the (B) resolves up as we would expect it to (to C).

) resolves down by step in the bass, and the (B) resolves up as we would expect it to (to C).

Example 31‑3. Transcription of Lin-Manuel Miranda, “You’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, 0:00–0:05

Listen to the full track, performed by Jonathan Groff, on Spotify.

Learn about American composer and lyricist Lin-Manuel Miranda (b. 1980) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Elizabeth Craft.

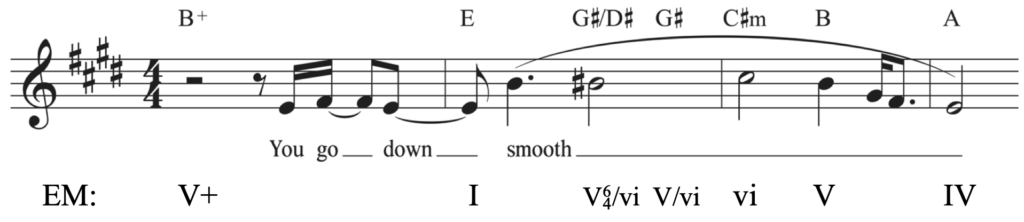

Examples 31-4 through 31-6 tonicize the submediant triad by using the V/vi or V7/vi.

Example 31‑4. Transcription of Sam Smith, “I’m Not the Only One,” 0:00–0:11

Example 31‑5. Transcription of Lake Street Dive, “You Go Down Smooth,” 1:20–1:26

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about 21st-century American pop/rock band Lake Street Dive by reading this Wikipedia article.

Example 31‑6. Transcription of Ray LaMontagne, “You Are the Best Thing,” 0:00–0:05

Listen to the audio examples featured in this chapter here: Spotify playlist for secondary dominants

Spelling secondary dominants

Follow these steps for success in spelling secondary dominants:

Step 1. Identify the root of the chord that is to be tonicized.

Step 2. For a moment, disregard the tonic key.

Step 3. Identify the dominant scale degree of the temporarily tonicized key identified in step 1. This is the root of the secondary dominant.

Step 4. Given the root identified in step 3, spell a MAmi7 chord (or major triad if not a seventh chord).

Step 5. Consider the overall tonic key once again, adding accidentals as needed, when spelling the chord rendered in step 4.

Figure 31-1 illustrates how to work through the process of spelling a secondary dominant, using V7/iii in the key of A major.

Figure 31‑1. Illustration of spelling a secondary dominant

Goal: to spell V7/iii in the key of A major.

- In A major, the root of the iii chord is C

.

. - Temporarily disregard the key of A major.

- The dominant scale degree of C

is G

is G . Therefore, the root of V7/iii is G

. Therefore, the root of V7/iii is G .

. - A major-minor 7th chord built on G

is: G

is: G B

B D

D F

F .

.

Spelling the chord in A major would look like this:

Video: T55 Spelling secondary dominants (11:21)

This video walks you through the steps needed to spell any secondary dominant chord, using the first three problems from Exercise 31-1 as models.

EXERCISE 31-1 Spelling secondary dominants

Spell the secondary dominants below. For each problem, provide the key signature of the tonic key and spell the secondary dominant using accidentals as needed. An example is provided.

EXAMPLE:

SET 1

SET 2

SET 3

SET 4

Secondary dominants in major keys

Now that we’ve explored what secondary dominants look like in musical contexts and spelled a few, let’s more systematically listen to and examine the chromatic chords in major keys that appear in the progressions in Example 31‑7. Each of these secondary dominants immediately resolves to the chord that is tonicized. On the right side, you will see the , which is the leading tone of the tonicized key, as well as the solfege syllables used in the secondary dominant. Sometimes the secondary leading tone is the single chromatic note of the chord, as in the V7/V, V7/ii, and V7/vi. In contrast, for the V7/IV, the chromatic note is not the secondary leading tone, but rather the chordal seventh. Finally, the V7/iii has not one, but two chromatic notes: the secondary leading tone and the fifth of the chord.

Example 31‑7. Secondary dominants in major keys

Video: T56 Hearing secondary dominants in major keys (11:03)

This video walks you through Example 31‑7 in order to help you hear the five different secondary dominants available in major keys. We review the solfege syllables associated with each chord, identify the secondary leading tone, listen to each progression, and sing the part that uses the chromaticism in each one.

Secondary dominants in minor keys

Example 31‑8 shows all of the possible secondary dominants in minor keys. Study each example and make note of the secondary leading tone and solfege syllables used in each secondary dominant.

Example 31‑8. Secondary dominants in minor keys

Video: T57 Hearing secondary dominants in minor keys (11:41)

This video explores the five secondary dominants available in minor keys, as demonstrated in Example 31‑8, identifies the solfege syllables associated with each, and invites you to sing the parts that use chromaticism in each progression.

EXERCISE 31-2 Analysis with secondary dominants

PART A. After listening to and studying the excerpt in Worksheet example 31‑1, do the following:

- Identify the key of the passage.

- Each chord is boxed with a number. Which chords are secondary dominants? (Hint: there are two in this excerpt.)

- For the chords you listed in the previous question, what are the Roman numeral labels for each? And do they resolve as you would expect them to?

- Consider the chords in boxes 3 and 4. If you hear a cadence here, what type would it be?

- Consider the chords in boxes 13 and 14. What type of cadence is implied here?

- There is one in this passage. Which chord (by number) is the six-four, and which type is it (, , or )?

- Consider the passage in box 9. Why might the composer have used A

and B

and B here?

here? - If you have more time, write a Roman numeral analysis for the entire excerpt.

Worksheet example 31‑1. Joseph Bologne, String Quartet, op. 1, no. 4, mvt. 1, mm. 81–91[3]

Listen to the full track, performed by the Jean-Noel Molard String Quartet, on Spotify.

Access the excerpt, without annotations, at Expanding the Music Theory Canon.

Learn about French composer and violinist Joseph Bologne (1745–1799) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Gabriel Banat.

PART B. After listening and studying the excerpt in Worksheet example 31‑2, provide a Roman numeral analysis for mm. 9–16 on the blanks provided.

Worksheet example 31‑2. Franz Schubert, Ecossaisen, op. 18, no. 1, mm. 1–16[4]

Listen to the full track, performed by pianist Michael Endres, on Spotify.

Learn about Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Maurice J. E. Brown and others.

PART C. After listening to and studying the excerpt in Worksheet example 31‑3, do the following:

- Identify all of the chromatic chords in this piece. Assuming a of one chord per bar, which measures contain secondary dominants?

- Now provide a Roman numeral label (with figured bass as needed to show inversions) for each measure containing a secondary dominant and the measure following each one (the chords of resolution).

- What kind of cadence occurs in mm. 7–8? In mm. 15–16?

- There is a beginning in m. 9. Identify the and .

- There are 2 in this excerpt. In which measures do they occur? And which type of six-four are they (, , or ) and why?

Worksheet example 31‑3. Franz Schubert, Originaltänze, op. 9, no. 16, mm. 1–16[5]

Listen to the full track, performed by pianist Maria Bergmann, on Spotify.

Learn about Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Maurice J. E. Brown and others.

PART D. After listening and studying the excerpt in Worksheet example 31‑4, identify the key, provide a Roman numeral analysis, and label all circled non-chord tones.

Worksheet example 31‑4. Ludwig van Beethoven, Violin Sonata no. 6 in A major, mvt. 2, mm. 1–9[6]

Listen to the full track, performed by violinist Pamela Frank and pianist Claude Frank, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Joseph Kerman and others.

PART E. Study and listen to the excerpt in Worksheet example 31‑5. Although the piece as a whole is in the key of G minor, we will interpret this passage in the key of B![]() major. Please provide Roman numerals for the chords numbered from 1 to 11 in the key of B

major. Please provide Roman numerals for the chords numbered from 1 to 11 in the key of B![]() major. Pro tip: remember seventh chords can be !

major. Pro tip: remember seventh chords can be !

Worksheet example 31‑5. Niccolò Paganini, Caprice in G minor, op. 1 no. 6, mm. 11–14[7]

Listen to the full track, performed by violinist Itzhak Perlman, on Spotify.

Learn about Italian virtuoso violinist and composer Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Edward Neill.

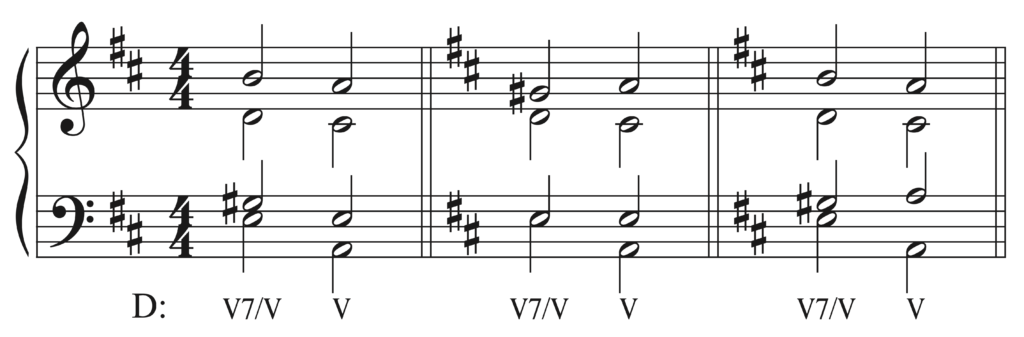

PART F. Study and listen to Worksheet example 31‑6. This excerpt uses the key signature of D major, but this portion is best analyzed in the key of C major. Please provide Roman numerals for each of the numbered chords in the key of C major.

Identify the secondary dominants. Which secondary dominant resolves as you would expect? Which one doesn’t, and why?

Worksheet example 31‑6. Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky, Violin Concerto in D major, op. 35, mvt. 1, mm. 162–67[8]

Listen to the full track, performed by Itzhak Perlman and the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Eugene Ormandy, on Spotify.

Learn about Russian composer Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Roland John Wiley.

Harmonic dictation with secondary dominants

To hone your aural skills, you can practice notating short progressions that use secondary dominants. To this end, Appendix E, nos 18–22, contains dictations with these chords. To practice this skill, listen to each short progression up to four times with the goals of notating the soprano and bass voices, providing Roman numerals beneath the staff, and identifying the cadence. Some students find it helpful to listen for the chromatic chords and/or secondary leading tones in the first or second hearing, marking the chords outside of the key and then determining the diatonic chord of resolution from the greater context. As with other harmonic dictation exercises we have done to date, all notes in the soprano and bass voices will be chord tones.

Voice leading with secondary dominants

Secondary dominants are connected to their respective chords of resolution in the same way as diatonic dominant sevenths. If you need a reminder of these principles, review the section of Chapter 25 titled “Voice leading with V7 and its inversions.”

The following summarizes best practices for resolving secondary dominants:

- Since the seventh of the V7 is considered a dissonance, it needs special preparation. When possible, prepare the seventh by the same note; otherwise, use stepwise motion.

- Resolve the seventh of the chord down by step to the third of the resolution chord.

- Resolve the , which is the third of the chord, up by step to the root of the resolution chord, unless it appears in an inner voice, in which case you may “” it.

- Resolve all other voices using same-note or stepwise motion whenever possible.

- For all inverted seventh chords, both the secondary dominant and chord of resolution should be complete (no omitted fifths).

When resolving root-position secondary dominants to root-position chords of resolution, three models are possible, illustrated in Example 31‑9:

- Bar 1: Complete seventh chord to complete triad (requires frustrating the secondary leading tone, possible only if the leading tone is in the alto or tenor voice)

- Bar 2: Incomplete seventh chord to complete triad (allows secondary leading tone to resolve up)

- Bar 3: Complete seventh chord to incomplete triad (allows secondary leading tone to resolve up)

Video: T58 Part writing with secondary dominants (10:54)

This video walks you through three possible resolutions of a root position secondary dominant (Example 31-9).

EXERCISE 31-3 Part writing with secondary dominants

Provide a key signature for each progression and realize each two-chord progression in four parts (), following these guidelines:

For all root-position seventh chords, choose one of the following resolution patterns and label which type of resolution you have chosen above the staff:

- Complete seventh chord to complete triad (requires frustrating the secondary leading tone, possible only if the leading tone is in the alto or tenor voice)

- Incomplete seventh chord to complete triad (allows secondary leading tone to resolve up)

- Complete seventh chord to incomplete triad (allows secondary leading tone to resolve up)

SET 1

SET 2

EXERCISE 31-4 Error detection with secondary dominants part writing

There’s something wrong with each of these. Your mission is to figure out what is wrong and how to fix it. Create a better solution on a separate piece of staff paper.

(1)

(2)

(3)

Supplemental resources for Chapter 31

- "Symphony No.94 in G major, Hob.I:94 (Haydn, Joseph)" by Paul-Gustav Feller is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Annotations are mine. ↵

- "Symphony No.1, Op.21 (Beethoven, Ludwig van)" by CCARH Team is licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0. Annotations are mine. ↵

- Example from https://www.expandingthemusictheorycanon.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/SD_Boulogne_String-Quartet-No.-4-in-C-Minor-Op.-1_Allegro-Moderato.pdf ↵

- Example from https://musictheoryexamples.com/ by Timothy Cutler ↵

- Example from https://musictheoryexamples.com/ by Timothy Cutler ↵

- Example from https://musictheoryexamples.com/ by Timothy Cutler ↵

- Example from https://musictheoryexamples.com/ by Timothy Cutler ↵

- Example from https://musictheoryexamples.com/ by Timothy Cutler ↵

any chord that temporarily functions as a dominant to a diatonic major or minor chord that is not tonic

system of associating pitches with syllables, also referred to as "solmization"; with movable-do solfege, the major scale uses "do," "re," "mi," "fa," "sol," "la," and "ti," and "do" is always tonic; with fixed-do solfege, "do" is always C

term referring to notes within a key

term referring to notes outside of a key

process in which a secondary dominant appears, temporarily destabilizing the tonic key and resolving to a different, albeit momentary, new tonic

a triad that has the root and third, but omits the fifth; or a seventh chord that has the root, third, and seventh, but omits the fifth

position of a chord when its seventh is the lowest sounding note

in a secondary dominant chord, the leading tone of the tonicized key

position of a chord when its fifth is the lowest sounding note

type of second inversion triad whose bass note is preceded by step and resolved by step in the same direction

type of second inversion triad that has scale degree 5 in the bass and resolves to a dominant chord, extending dominant function, usually at a cadence

type of second inversion triad with an embellishing function by keeping the bass note of the chord preceding and following it

the rate of chord change

process in which a portion of music (both intervallic and rhythmic content) is successively replicated at a different pitch level

with regard to melodic sequence, the first iteration of sequential material

with regard to melodic sequence, term referring to each subsequent iteration of sequential material, following the initial model

triad in second inversion, meaning the fifth of the chord is the lowest sounding note

part-writing process in which instead of the leading tone resolving up to tonic, it resolves to the fifth of the tonic chord (scale degree 7 goes to 5 instead of 1), possible only when the leading tone is in an inner voice (alto or tenor)

abbreviation for four-voice music, referring to soprano, alto, tenor, bass; may apply to choral music or instrumental music in four parts