Main Body

18 Sequence and uses of the mediant

Learning goals for Chapter 18

In this chapter, we will learn:

- How melodic sequences are structured

- How to write melodic sequences

- Common types of harmonic sequences

- How to identify melodic and harmonic sequences in musical contexts

- Ways in which the mediant triad is used

Melodic sequence

is a common compositional device that relies on a series of successively occurring rhythmic, melodic, and/or harmonic patterns. occurs anytime a portion of music (both intervallic and rhythmic content) is immediately replicated at a different pitch level. The first iteration of a sequence is called the , and each subsequent iteration is called a . Example 18-1 contains a transcription of a recording by Mitski that uses a melodic sequence. The model features intervals of a descending sixth followed by an ascending fifth, and each leg begins a third lower than the previous iteration.

Example 18‑1. Transcription of Mitski, “Washing Machine Heart,” 1:10–1:24

Melodic sequences can be either real (exact) or tonal. maintain the exact intervallic qualities in each leg of the sequence. maintain the quantity (number) of each interval, but not the quality, in order to fit within a key. The melodic sequence in Example 18‑1 is tonal because all the notes are diatonic in the key of the excerpt (A major). It is rewritten as a real sequence in Example 18-2, using chromaticism to preserve the exact intervallic structure of the initial model (mi6 descending followed by P5 ascending) in each leg. Most melodic sequences we encounter in tonal music will be , not , sequences.

While melodic sequences are common in a variety of styles, they are especially common in Baroque music. The music of J. S. Bach, one of the most famous European composers of the Baroque era, features melodic sequences with great frequency. Example 18‑3 shows a representative passage, annotated to show three melodic sequences from Bach’s Violin Sonata in G minor. The first, in m. 90, states the model starting on B![]() , and the leg that follows starts a step higher. The second sequence in this passage occurs in the following measure and contains the model starting on C

, and the leg that follows starts a step higher. The second sequence in this passage occurs in the following measure and contains the model starting on C![]() , followed by no fewer than four complete legs, each starting a step lower than the previous one. The sequence breaks before the completion of what would have been the fifth leg. The final sequence in this passage occurs in m. 93. Each leg following the model begins a third lower than the previous segment.

, followed by no fewer than four complete legs, each starting a step lower than the previous one. The sequence breaks before the completion of what would have been the fifth leg. The final sequence in this passage occurs in m. 93. Each leg following the model begins a third lower than the previous segment.

Example 18‑3. J. S. Bach, Violin Sonata in G minor, Fuga, mm. 90–94

Listen to the full track, performed by violinist Hilary Hahn, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Christoph Wolff and Walter Emery.

Harmonic sequence

Sequences may also be harmonic. occurs when a repeating pattern of root motion appears in a harmonic progression. This list is not exhaustive, but three common harmonic sequences include root motion:

- by fifth (circle-of-fifths)

- down a fourth, up a second (↓4 ↑2)

- by falling thirds

Each of these types is shown in the examples below.

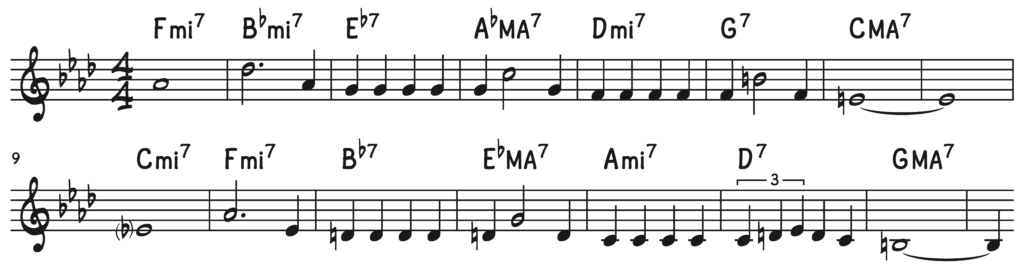

Example 18‑4. Circle-of-fifths sequence in Jerome Kern, “All the Things You Are,” with harmonization as performed by Michael Jackson

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about American musical theater composer Jerome Kern (1885–1945) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Ronald Byrnside and Andrew Lamb.

Example 18‑5. ↓4 ↑2 sequence in Johann Pachelbel, Canon in D, mm. 1–7

Listen to the full track, performed by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Ewald V. Nolte and revised by John Butt.

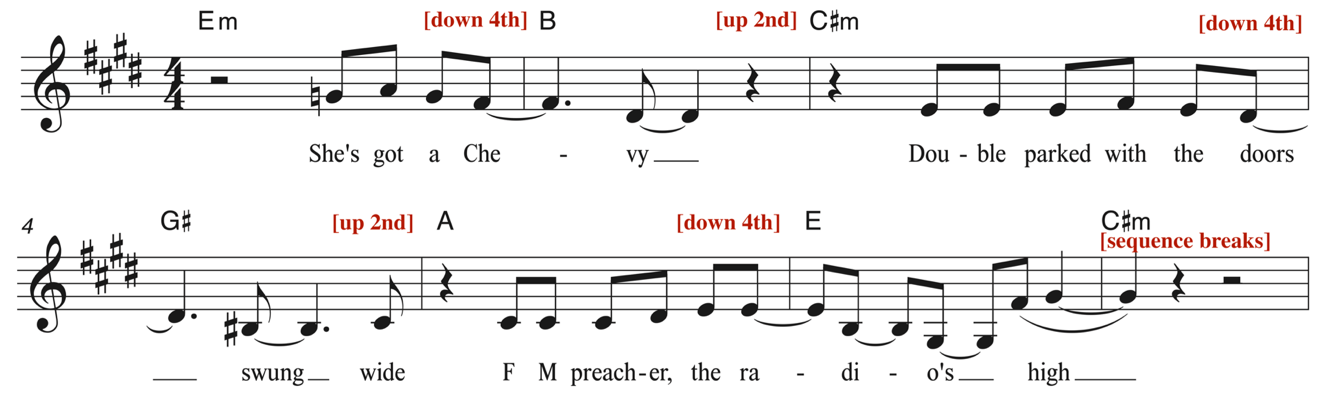

Example 18‑6. Transcription of ↓4 ↑2 sequence in Bachelor, “Stay in the Car,” 0:00–0:16

Example 18‑7. Transcription of falling thirds sequence in Gene Chandler, “Duke of Earl,” 0:00–0:11

Video: T41 Sequence (7:30)

This video introduces melodic and harmonic sequences and features the musical examples by Mitski, Michael Jackson, Pachelbel, and Gene Chandler shown above. Please note that in the Michael Jackson example, Dmi7 is used in lieu of D![]() MA7 in m. 5, and Ami7 instead of A

MA7 in m. 5, and Ami7 instead of A![]() MA7 in m. 13. See Example 18‑4 above for a more accurate harmonic transcription.

MA7 in m. 13. See Example 18‑4 above for a more accurate harmonic transcription.

EXERCISE 18-1 Analysis with sequence

After listening to each excerpt, complete a Roman numeral analysis, label cadences, and identify the texture and type of harmonic sequence. When a melodic sequence is also present, bracket and label the model and each leg of the sequence above the staff. For the harmonic analysis, disregard non-chord tones, which appear in parentheses.

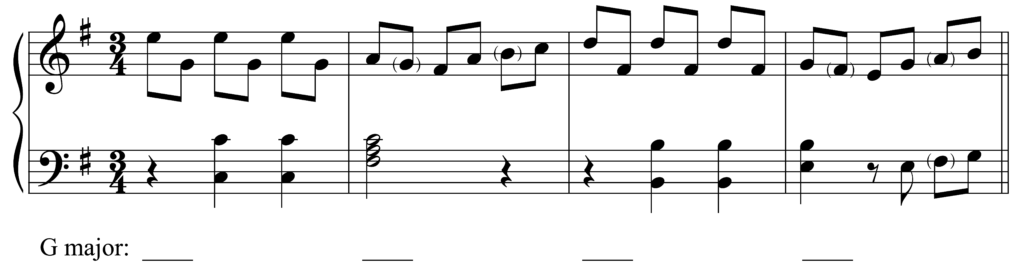

Worksheet example 18‑1. George Frideric Handel, Courante, mm. 5–8

Texture: ______________________

Harmonic sequence root motion: ______________________

Listen to an arrangement of the piece in its entirety, performed by guitarist John Williams, on Spotify.

Learn about English composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Anthony Hicks.

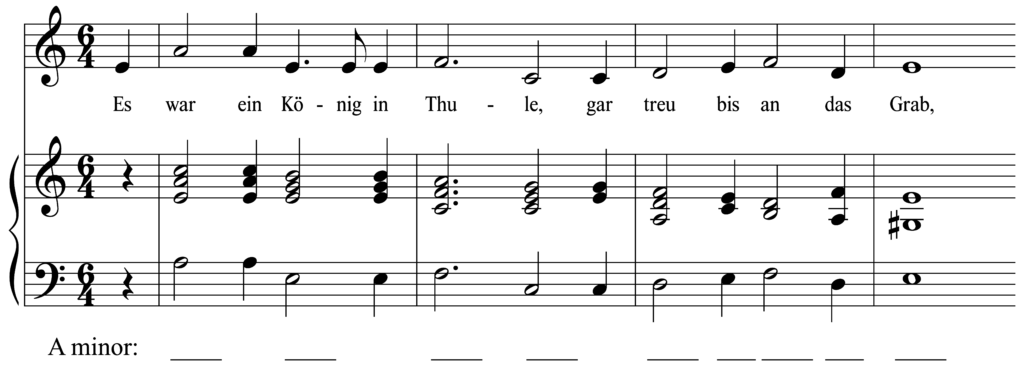

Worksheet example 18‑2. Carl Friedrich Zelter, Der König in Thule, mm. 1–4

Texture: ______________________

Harmonic sequence root motion: ______________________

Listen to an arrangement of the piece in its entirety, performed by Carl Maria von Weber Men’s choir, on Spotify.

Read an English translation of the song text at the Oxford International Song Festival website.

Learn about German composer and conductor Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Hans-Günter Ottenberg.

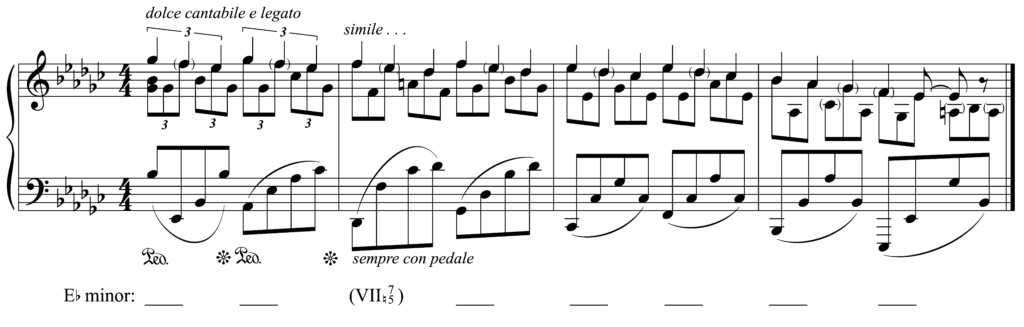

Worksheet example 18‑3. Amy Marcy Cheney Beach, “A Hermit Thrush at Eve,” op. 92, no. 1, mm. 10–13

Texture: ______________________

Harmonic sequence root motion: ______________________

Listen to the full track, performed by pianist Christopher O’Riley, on Spotify.

Learn about American composer and pianist Amy Marcy Cheney Beach (1867–1944) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Adrienne Fried Block and revised by E. Douglas Bomberger.

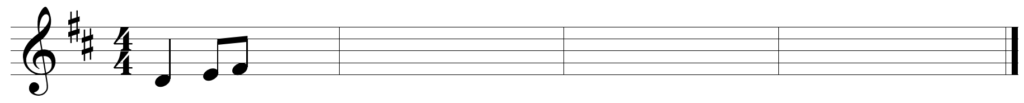

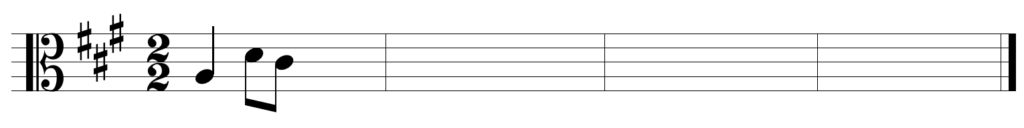

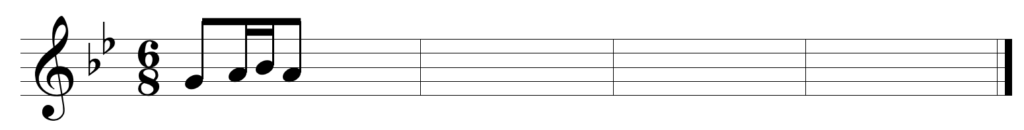

EXERCISE 18-2 Creating melodic sequences

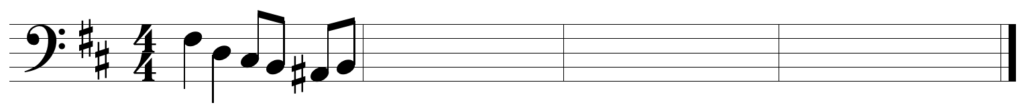

Given the model, create a tonal melodic sequence by adding one or two legs and then complete the melody logically (following the principles we’ve studied in Chapter 15) in the blank measures that follow. First determine the most logical key, based on the key signature and other musical cues. Each melody should end on tonic. Bracket and label the model and each leg of the sequence. The first is done for you.

EXAMPLE. The given model:

EXERCISE 18-3 Composing a melody with sequence

On staff paper or using a notation program, compose a melody of four to eight bars in length. The melody should have a melodic sequence (comprising the initial model, no longer than one bar in length, and two subsequent legs) and a conclusive tonal cadence (implying either a or ).

As with all tonal compositions, your melody should have a clef, key signature, time signature, and bar lines. All systems after the first should continue to have a clef, key signature, and bar lines.

You may find it useful to sketch some ideas first on a separate sheet of manuscript paper before copying your composition neatly in its final form.

Melodic dictation with sequences

You can hone your aural skills by notating melodies that use melodic sequence. See nos. 23–27 in Appendix D for melodic dictations using sequence.

Uses of the mediant

Unlike all of the other diatonic triads we have studied, the mediant triad appears less often. It is perhaps the least versatile of all chords because it usually appears in one of the following specific contexts:

- Part of a harmonic sequence

- An extension of in the progression I – iii – IV – V (or i – III – iv – V in minor), often harmonizing a descending melody, with scale-degrees

–

–  –

–  –

–

Example 18‑8 shows how the mediant triad works with the ↓4 ↑2 sequence, made famous by Pachelbel’s Canon. The mediant triad may appear in other sequences as well, such as the circle-of-fifths sequence.

Example 18‑8. Johann Pachelbel, Canon in D, mm. 1–2

Listen to the full track, performed by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, on Spotify.

Learn about German composer Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706) by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Ewald V. Nolte and revised by John Butt.

Example 18‑9 shows the voice-leading context for the use of the mediant with the I – iii – IV – V progression.

Example 18‑10 uses this progression in the key of G major (I – iii – IV – V), and Example 18‑11 uses a similar progression in A major (I – iii – IV – I).

Example 18‑10. Ronnie Milsap, “Smoky Mountain Rain,” 0:48–1:20

Example 18‑11. Peter, Paul, and Mary, “Puff, the Magic Dragon,” 0:39–0:45

Listen to the full track on Spotify.

Learn about 20th-century American folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary by reading this Oxford Music Online article, written by Richard D. Driver.

Occasionally the mediant triad functions as a substitute for dominant (this occurs in a handful of late 19th-century compositions, as well as a few pop tunes). However, since it shares scale degrees ![]() and

and ![]() with the tonic triad, and

with the tonic triad, and ![]() and

and ![]() with the dominant triad, it is generally a less effective and less clear means of conveying than the dominant or leading tone chords.

with the dominant triad, it is generally a less effective and less clear means of conveying than the dominant or leading tone chords.

Video: T42 Uses of the mediant (5:51)

This video shows you the two ways the mediant triad is used in most tonal music: (1) as part of a larger harmonic sequence and (2) as an extension of tonic function in the chord progression I – iii – IV. This video features the musical examples by Pachelbel, Ronnie Milsap, and Peter, Paul, and Mary shown above.

Supplemental resources for Chapter 18

a common compositional process that uses a series of successively occurring rhythmic, melodic, and/or harmonic patterns

process in which a portion of music (both intervallic and rhythmic content) is successively replicated at a different pitch level

with regard to melodic sequence, the first iteration of sequential material

with regard to melodic sequence, term referring to each subsequent iteration of sequential material, following the initial model

type of melodic sequence that replicates the exact intervallic profile (both quantity and quality) of all intervals of the model, regardless of the key

type of melodic sequence that maintains the quantity (number) of each interval, but not necessarily the quality, in order to fit within a key

process in which a repeating pattern of root motion appears in a harmonic progression

abbreviation for "perfect authentic cadence," which is the most conclusive cadence type, having both of the following features: (1) the cadence uses a dominant chord in root position followed by a tonic chord in root position, and (2) the tonic triad uses scale degree 1 (“do”) in the soprano melody or main melodic part

abbreviation for "imperfect authentic cadence," which refers to any cadence that moves from dominant function to the tonic triad in which any of the chords is inverted or uses the leading tone chord instead of V, or in which a scale degree other than 1 ("do") is in the highest part or melody with the tonic chord

the most stable tonal function of repose, resolution, or conclusion, exemplified by the triad built on scale degree 1

the most unstable tonal function characterized by tension, setting up a listener’s expectation to hear tonic as a resolution; chords with dominant function include the dominant triad, dominant seventh, and chords built on the leading tone